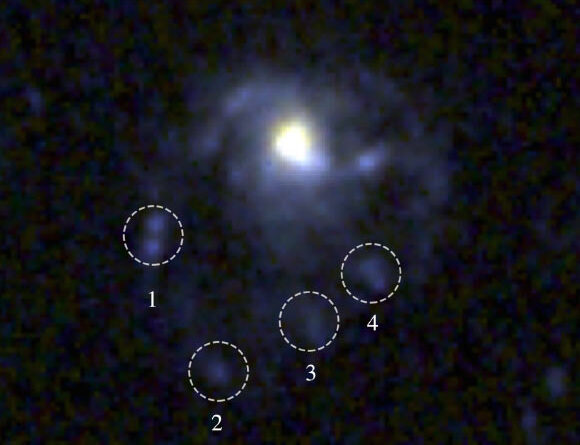

(Image credit: Yashuv, Grosman, 2024, PLOS One, CC-BY 4.0)

Archaeologists in Israel have identified what may be one of the earliest examples of wheel-like technology ever found: several dozen 12,000-year-old, doughnut-shaped pebbles that might be spindle whorls.

The roughly 100 spindle whorls are pebbles with holes that allow a stick to be inserted to make it easier to spin textiles using flax or wool, according to the study, which was published Wednesday (Nov. 13) in the journal PLOS One.

“This collection of spindle whorls would represent a very early example of humans using rotation with a wheel-shaped tool,” the archaeologists wrote in a statement. “They might have paved the way for later rotational technologies, such as the potter’s wheel and the cart wheel, which were vital to the development of early human civilizations.”

“While the perforated pebbles were kept mostly at their natural unmodified shape, they represent wheels in form and function: a round object with a hole in the centre connected to a rotating axle,” Talia Yashuv, a graduate student at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Institute of Archaeology and co-author of the paper, told Live Science in an email.

Related: 1st wheel was invented 6,000 years ago in the Carpathian Mountains, modeling study suggests

Studying pebbles

Archaeologists agree that the wheel was invented around 6,000 years ago, although its exact origins are unknown. To investigate whether the pebbles were early “rotational technologies,” Yashuv and study co-author Leore Grosman, a professor of prehistoric archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology, analyzed more than 100 holey limestone pebbles, which weighed anywhere between 0.043 and 1.2 ounces (1 gram and 34 grams), they wrote in the study.

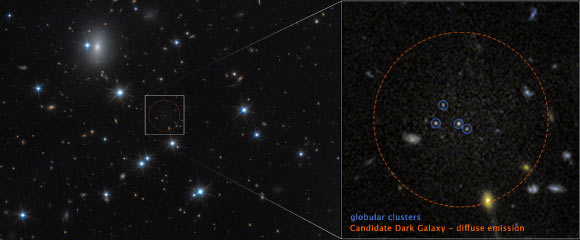

The pebbles were found in previous excavations at a site archaeologists call “Nahal Ein Gev II.” It is located in northern Israel, about 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) east of the Sea of Galilee. It dates back around 12,000 years, before people in the region practiced agriculture on a large scale.

The team used 3D scanning technology to create detailed virtual models of the pebbles. This allowed the archaeologists to analyze the pebbles at a level of detail that the human eye could not. They found that most of the pebbles have holes drilled into their centers.

The team examined several possible uses for the pebbles. For example, they considered whether the pebbles could have been beads. However, beads are often carved into precise shapes, tend to be lightweight and usually don’t exceed 0.07 ounce (2 grams), making this an unlikely use for the pebbles, the team said. It’s also unlikely that the pebbles were fishing weights, because there are no other examples of fishing weights from such an early date, the researchers found. They also noted that early fishing weights tended to be larger and made out of heavier material than limestone.

To see if the pebbles could have been spindle whorls, the team created precise replicas of the pebbles using the 3D scans and had Yonit Crystal, an expert in traditional craft making, use them to spin textiles. With some practice, Crystal was able to spin textiles effectively, finding that flax was easier to work with than wool.

The team concluded that most of the pebbles were likely used as spindle whorls, an early type of wheel-and-axle technology.

The team’s findings are important, said Alex Joffe, an archaeologist who has conducted extensive work in the region’s prehistoric archaeology and is the director of strategic affairs for the Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa. “The experimental results do indeed suggest the perforated stones were used as spindle whorls,” Joffe, who was not involved with the study, told Live Science in an email.

“It is probable that flax was being spun in small quantities for use in other emerging technologies such as bags and fishing lines, that is to say new methods of storage and subsistence,” Joffe said.

If the spindle whorls were used to create new methods of storage, then “the technological implications may be even larger than the authors suggested,” Joffe said.

Yorke Rowan, an archaeology professor at the University of Chicago, also praised the research. “I think this is a great piece of analysis, thorough and convincing,” Rowan told Live Science in an email. “Because these are so early, I think that the assessment that this is a critical turning point [in] technological achievement is well founded,” Rowan said.

However, Carole Cheval, a researcher with expertise in prehistoric textiles who is an associate researcher at an archaeological laboratory known as Cultures and Environment, Prehistory, Antiquity, Middle Ages (CEPAM) in France, noted that the finding isn’t the oldest evidence of wheel-like technology.

In an email to Live Science, Cheval said that “the objects presented in this article may well be spindle whorls; indeed, the hypothesis is not original and other similar objects, some older, have been published.”

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.