“The [structural] mechanism producing these problematic outcomes is really robust and hard to resolve.”

Credit: Aurich Lawson|Getty Images

Credit: Aurich Lawson|Getty Images

It’s obvious that much of social networks has actually ended up being exceptionally inefficient. Instead of bringing us together into one utopian public square and promoting a healthy exchange of concepts, these platforms frequently produce filter bubbles or echo chambers. A little number of prominent users amass the lion’s share of attention and impact, and the algorithms developed to optimize engagement wind up simply enhancing outrage and dispute, making sure the supremacy of the loudest and most severe users– consequently increasing polarization a lot more.

Various platform-level intervention techniques have actually been proposed to fight these concerns, however according to a preprint published to the physics arXiv, none are most likely to be efficient. And it’s not the fault of much-hated algorithms, non-chronological feeds, or our human predisposition for looking for negativeness. Rather, the characteristics that trigger all those unfavorable results are structurally embedded in the really architecture of social networks. We’re most likely doomed to unlimited poisonous feedback loops unless somebody strikes upon a dazzling essential redesign that handles to alter those characteristics.

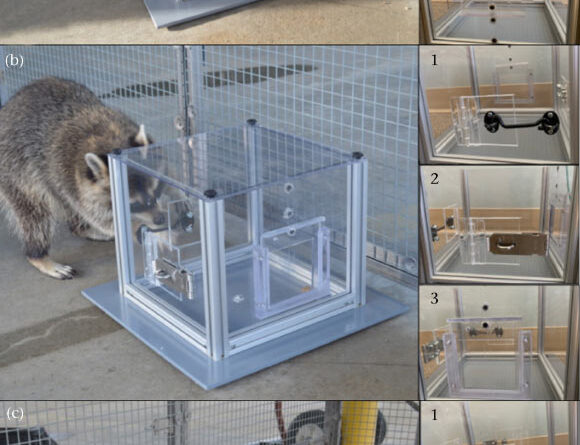

Co-authors Petter Törnberg and Maik Larooij of the University of Amsterdam wished to discover more about the systems that generate the worst elements of social networks: the partisan echo chambers, the concentration of impact amongst a little group of elite users (attention inequality), and the amplification of the most severe dissentious voices. They integrated basic agent-based modeling with big language designs (LLMs), basically producing little AI personalities to imitate online social media habits. “What we found is that we didn’t need to put any algorithms in, we didn’t need to massage the model,” Törnberg informed Ars. “It just came out of the baseline model, all of these dynamics.”

They then checked 6 various intervention methods social researchers have actually been proposed to counter those results: changing to sequential or randomized feeds; inverting engagement-optimization algorithms to decrease the presence of extremely reposted mind-blowing material; enhancing the variety of perspectives to expand users’ direct exposure to opposing political views; utilizing “bridging algorithms” to raise material that cultivates good understanding instead of psychological justification; concealing social stats like reposts and fan accounts to minimize social impact hints; and eliminating bios to restrict direct exposure to identity-based signals.

The outcomes were far from motivating. Just some interventions revealed modest enhancements. None had the ability to totally interrupt the essential systems producing the inefficient impacts. Some interventions really made the issues even worse. Sequential buying had the greatest result on lowering attention inequality, however there was a tradeoff: It likewise magnified the amplification of severe material. Bridging algorithms substantially deteriorated the link in between partisanship and engagement and decently enhanced perspective variety, however it likewise increased attention inequality. Enhancing perspective variety had no considerable effect at all.

Is there any hope of discovering reliable intervention techniques to fight these bothersome elements of social media? Or should we obliterate our social networks accounts completely and go reside in caverns? Ars overtook Törnberg for a prolonged discussion to read more about these unpleasant findings.

Ars Technica: What drove you to perform this research study?

Petter Törnberg: For the last 20 years or two, there has actually been a lots of research study on how social networks is improving politics in various methods, generally utilizing observational information. In the last couple of years, there’s been a growing cravings for moving beyond simply grumbling about these things and attempting to see how we can be a bit more positive. Can we determine how to enhance social networks and produce online areas that are really measuring up to those early pledges of offering a public sphere where we can ponder and discuss politics in a useful method?

The issue with utilizing observational information is that it’s extremely tough to evaluate counterfactuals to execute alternative options. One kind of approach that has actually existed in the field is agent-based simulations and social simulations: develop a computer system design of the system and then run experiments on that and test counterfactuals. It works for taking a look at the structure and development of network characteristics.

At the very same time, those designs represent representatives as basic guideline fans or optimizers, and that does not record anything of the cultural world or politics or human habits. I’ve constantly been of the questionable viewpoint that those things really matter, particularly for online politics. We require to study both the structural characteristics of network developments and the patterns of cultural interaction.

Ars Technica: So you established this hybrid design that integrates LLMs with agent-based modeling.

Petter Törnberg: That’s the service that we discover to move beyond the issues of traditional agent-based modeling. Rather of having this easy guideline of fans or optimizers, we utilize AI or LLMs. It’s not a best option– there’s all type of predispositions and constraints– however it does represent an advance compared to a list of if/then guidelines. It does have something more of catching human habits in a more possible method. We provide personalities that we receive from the American National Election Survey, which has extremely comprehensive concerns about United States citizens and their pastimes and choices. And after that we turn that into a textual personality– your name is Bob, you’re from Massachusetts, and you like fishing– simply to provide something to speak about and a bit richer representation.

And after that they see the random news of the day, and they can select to publish the news, checked out posts from other users, repost them, or they can pick to follow users. If they pick to follow users, they take a look at their previous messages, take a look at their user profile.

Our concept was to begin with the very little bare-bones design and after that include things to attempt to see if we might recreate these bothersome effects. To our surprise, we in fact didn’t have to include anything since these troublesome repercussions simply came out of the bare bones design. This broke our expectations and likewise what I believe the literature would state.

Ars Technica: I’m hesitant of AI in basic, especially in a research study context, however there are extremely particular circumstances where it can be very helpful. This strikes me as one of them, mainly due to the fact that your fundamental design showed to be so robust. You got the very same characteristics without presenting anything additional.

Petter Törnberg: Yes. It’s been a huge discussion in social science over the last 2 years approximately. There’s a lots of interest in utilizing LLMs for social simulation, however nobody has actually determined for what or how it’s going to be useful, or how we’re going to get past these issues of credibility and so on. The type of technique that we take in this paper is constructing on a custom of complex systems believing. We envision really basic designs of the human world and attempt to record extremely basic systems. It’s not truly intending to be reasonable or an accurate, total design of human habits.

I’ve been among the more important individuals of this approach, to be sincere. At the exact same time, it’s difficult to picture any other method of studying these type of characteristics where we have cultural and structural elements feeding back into each other. I still have to take the findings with a grain of salt and understand that these are designs, and they’re catching a kind of theoretical world– a round cow in a vacuum. We can’t anticipate what somebody is going to have for lunch on Tuesday, however we can catch wider systems, and we can see how robust those systems are. We can see whether they’re steady, unsteady, which conditions they emerge in, and the basic limits. And in this case, we discovered a system that appears to be extremely robust.

Ars Technica: The dream was that social networks would assist rejuvenate the general public sphere and support the sort of useful political discussion that your paper considers “vital to democratic life.” That mostly hasn’t taken place. What are the main unfavorable unanticipated effects that have emerged from social networks platforms?

Petter Törnberg: First, you have echo chambers or filter bubbles. The danger of broad arrangement is that if you wish to have a working political discussion, working consideration, you do require to do that throughout the partisan divide. If you’re just having a discussion with individuals who currently concur with each other, that’s inadequate. There’s dispute on how extensive echo chambers are online, however it is rather developed that there are a great deal of areas online that aren’t really useful due to the fact that there’s only individuals from one political side. That’s one component that you require. You require to have a variety of viewpoint, a variety of viewpoint.

The 2nd one is that the consideration requires to be amongst equates to; individuals require to have basically the exact same impact in the discussion. It can’t be totally managed by a little, elite group of users. This is likewise something that individuals have actually indicated on social networks: It tends of producing these influencers due to the fact that attention brings in attention. And after that you have a breakdown of discussion amongst equates to.

The last one is what I call (based upon Chris Bail’s book) the social networks prism. The more severe users tend to get more attention online. This is frequently gone over in relation to engagement algorithms, which tend to recognize the kind of material that a lot of upsets us and after that increase that material. I describe it as a “trigger bubble” rather of the filter bubble. They’re attempting to activate us as a method of making us engage more so they can extract our information and keep our attention.

Ars Technica: Your conclusion is that there’s something within the structural characteristics of the network itself that’s to blame– something essential to the building and construction of social media networks that makes these very challenging issues to fix.

Petter Törnberg: Exactly. It originates from the reality that we’re utilizing these AI designs to record a richer representation of human habits, which permits us to see something that would not actually be possible utilizing traditional agent-based modeling. There have actually been previous designs taking a look at the development of social media networks on social networks. Individuals select to retweet or not, and we understand that action tends to be extremely reactive. We tend to be extremely psychological because option. And it tends to be an extremely partisan and polarized kind of action. You struck retweet when you see somebody being upset about something, or doing something dreadful, and after that you share that. It’s popular that this causes hazardous, more polarized material spreading out more.

What we discover is that it’s not simply that this material spreads; it likewise forms the network structures that are formed. There’s feedback in between the efficient psychological action of picking to retweet something and the network structure that emerges. And after that in turn, you have a network structure that feeds back what material you see, leading to a harmful network. The meaning of an online social media is that you have this type of publishing, reposting, and following characteristics. It’s rather basic to it. That alone appears to be sufficient to drive these unfavorable results.

Ars Technica: I was honestly shocked at the ineffectiveness of the numerous intervention methods you evaluated. It does appear to discuss the Bluesky dilemma. Bluesky has no algorithm, for instance, yet the exact same characteristics still appear to emerge. I believe Bluesky’s creators truly wish to prevent those inefficient problems, however they may not prosper, based upon this paper. Why are such interventions so inefficient?

Petter Törnberg: We’ve been going over whether these things are because of the platforms doing wicked things with algorithms or whether we as users are selecting that we desire a bad environment. What we’re stating is that it does not need to be either of those. This is typically the unexpected results from interactions based upon underlying guidelines. It’s not always due to the fact that the platforms are wicked; it’s not always since individuals wish to remain in hazardous, dreadful environments. It simply follows from the structure that we’re supplying.

We checked 6 various interventions. Google has actually been attempting to make social networks less hazardous and just recently launched a newsfeed algorithm based upon the material of the text. That’s one example. We’re likewise attempting to do more subtle interventions because typically you can discover a specific method of pushing the system so it switches to much healthier characteristics. A few of them have moderate or somewhat favorable results on among the characteristics, however then they frequently have unfavorable results on another characteristic, or they have no effect whatsoever.

I ought to state likewise that these are extremely severe interventions in the sense that, if you depended upon earning money on your platform, you most likely do not wish to execute them due to the fact that it most likely makes it truly tiring to utilize. It’s like revealing the least prominent users, the least retweeted messages on the platform. However, it does not actually make a distinction in altering the standard results. What we draw from that is that the system producing these troublesome results is truly robust and difficult to deal with offered the fundamental structure of these platforms.

Ars Technica: So how might one tackle developing an effective social media that does not have these issues?

Petter Törnberg: There are a number of instructions where you might envision going, however there’s likewise the restriction of what is popular usage. Reflect to the early Internet, like ICQ. ICQ had this function where you might simply link to a random individual. I enjoyed it when I was a kid. I would talk with random individuals all over the world. I was 12 in the countryside on a little island in Sweden, and I was speaking to somebody from Arizona, living a various life. I do not understand how effective that would be nowadays, the Internet having actually ended up being a lot less innocent than it was.

We can focus on the concern of inequality of attention, a really well-studied and robust function of these networks. I personally believed we would have the ability to resolve it with our interventions, however attention draws attention, and this causes a power law circulation, where 1 percent [of users] controls the whole discussion. We understand the conditions under which those power laws emerge. This is among the primary results of social media characteristics: severe inequality of attention.

In social science, we constantly teach that whatever is a regular circulation. The relocation from studying the standard social world to studying the online social world implies that you’re moving from these great typical circulations to these terrible power law circulations. Those are the results of having social media networks where the possibility of linking to somebody depends upon the number of previous connections they have. If we wish to eliminate that, we most likely need to move far from the social media network design and have some type of spatial design or group-based design that makes things a bit more regional, a bit less worldwide adjoined.

Ars Technica: It seems like you ‘d wish to prevent those huge prominent nodes that play such a main function in a big, intricate international network.

Petter Törnberg: Exactly. I believe that having those international networks and structures essentially weakens the possibility of the sort of discussions that political researchers and political theorists typically discussed when they were going over in the general public square. They were discussing social interaction in a coffee home or a tea home, or reading groups and so on. Individuals believed the Internet was going to be exactly that. It’s quite not that. The characteristics are basically various due to the fact that of those structural distinctions. We should not anticipate to be able to get a coffee home consideration structure when we have a worldwide social media network where everybody is linked to everybody. It is tough to envision a practical politics constructing on that.

Ars Technica: I wish to return to your talk about the power law circulation, how 1 percent of individuals control the discussion, due to the fact that I believe that is something that a lot of users consistently forget. The terrible things we see individuals state on the Internet are not always a sign of the huge bulk of individuals on the planet.

Petter Törnberg: For sure. That is recording 2 elements. The very first is the social networks prism, where the viewpoint we get of politics when we persevere the lens of social networks is essentially various from what politics in fact is. It appears a lot more harmful, far more polarized. Individuals appear a bit crazier than they truly are. It’s an extremely well-documented element of the increase of polarization: People have an incorrect understanding of the opposite. The majority of people have relatively sensible and relatively comparable viewpoints. The real polarization is lower than the viewed polarization. Which probably is an outcome of social networks, how it misrepresents politics.

And after that we see this really little group of users that end up being extremely prominent who typically end up being extremely noticeable as an outcome of being a bit insane and outrageous. Social network develops a reward structure that is truly main to improving not simply how we see politics however likewise what politics is, which political leaders end up being effective and prominent, due to the fact that it is managing the circulation of what is probably the most important kind of capital of our age: attention. Particularly for political leaders, having the ability to manage attention is the most crucial thing. And because social networks produces the conditions of who gets attention or not, it produces a reward structure where specific characters work much better in such a way that’s simply basically various from how it remained in previous ages.

Ars Technica: There are those who have actually sworn off social networks, however it looks like just not taking part isn’t actually a service, either.

Petter Törnberg: No. Even if you just check out, state, The New York Times, that paper is still improved by what works on social media, the social media reasoning. I had a trainee who did a little task this in 2015 revealing that as social networks ended up being more prominent, the headings of The New York Times ended up being more clickbaity and adjusted to the design of what dealt with social networks. Traditional media and our really culture is being changed.

More than that, as I was simply stating, it’s the type of political leaders, it’s the type of individuals who are empowered– it’s the whole culture. Those are the important things that are being changed by the power of the reward structures of social networks. It’s not like, “This is things that are happening in social media and this is the rest of the world.” It’s all knotted, and in some way social networks has actually ended up being the cultural engine that is forming our politics and society in extremely essential methods..

Ars Technica: I typically like to state that technological tools are essentially neutral and can be utilized for great or ill, however this time I’m not so sure. Exists any hope of discovering a method to take the harmful and turn it into a net favorable?

Petter Törnberg: What I would state to that is that we are at a crisis point with the increase of LLMs and AI. I have a tough time seeing the modern design of social networks continuing to exist under the weight of LLMs and their capability to mass-produce incorrect info or details that enhances these social media network characteristics. We currently see a great deal of stars– based upon this money making of platforms like X– that are utilizing AI to produce material that simply looks for to optimize attention. False information, frequently extremely polarized details– as AI designs end up being more effective, that material is going to take over. I have a difficult time seeing the standard social networks designs making it through that.

We’ve currently seen the procedure of individuals pulling back in part to reliable brand names and looking for to have gatekeepers. Youths, particularly, are entering into WhatsApp groups and other closed neighborhoods. Of course, there’s false information from social media dripping into those chats. These kinds of crisis points at least have the hope that we’ll see an altering circumstance. I would not wager that it’s a circumstance for the much better. You desired me to sound favorable, so I attempted my finest. Possibly it’s in fact “good riddance.”

Ars Technica: So let’s simply explode all the social networks networks. It still will not be much better, however a minimum of we’ll have various issues.

Petter Törnberg: Exactly. We’ll discover a brand-new ditch.

DOI: arXiv, 2025. 10.48550/ arXiv.2508.03385 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior author at Ars Technica with a specific concentrate on where science fulfills culture, covering whatever from physics and associated interdisciplinary subjects to her preferred movies and television series. Jennifer resides in Baltimore with her partner, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their 2 felines, Ariel and Caliban.

204 Comments

Learn more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.