(Image credit: Francesco Riccardo Iacomino/Getty Images)

Freshly found fossil imprints of ancient microbial nests recommend that scientists require to widen their look for the earliest life to much deeper and more unsteady locations.

The old and wrinkly fossil structures, discovered in the Central High Atlas Mountains of Morocco, are inscribed on turbidites, which are deposits set by undersea landslides. The scientists were shocked to see the imprints on these turbidites, due to the fact that many microbial mats today grow in shallow water, where photosynthetic germs can draw energy

from light infiltrating the waves.

Wrinkle structures “shouldn’t be in this deep-water setting,” Rowan Martindalea geobiologist at the University of Texas at Austin, stated in a declaration

Martindale is the lead author of a paper released Dec. 3 in the journal Geology explaining this unexpected discover. She stumbled– nearly actually– throughout the fossils while studying ancient reefs in Morocco’s Dadès Valley. While strolling, she saw wrinkly, ripple-like structures on the great sandstone and siltstone listed below her feet.

These wrinkle structures appeared like imprints of photosynthetic microbial mats, which are layered neighborhoods of germs that typically form on sediments in ponds, oceans and other bodies of water. Those fossils are normally older than 540 million years due to the fact that the fragile pattern is typically cleaned away by animal activity over time, and there were couple of animals before 540 million years earlier.

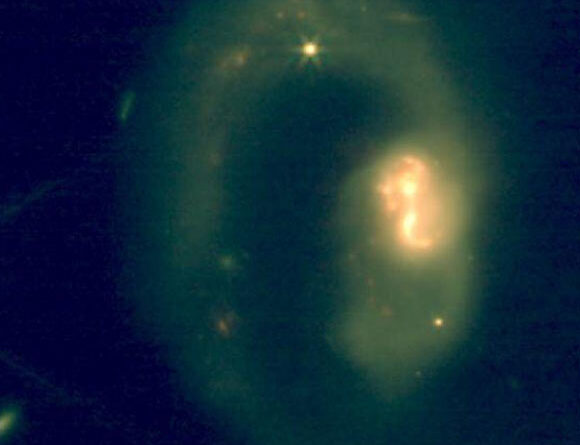

The wrinkle structures in the Tagoudite Formation of the Central High Atlas Mountains (Image credit: Retrieved from: Rowan C. Martindale, Sinjini Sinha, Travis N. Stone et al. Chemosynthetic microbial neighborhoods formed wrinkle structures in ancient turbidites. Geology 2025; doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/G53617.1 CC BY 4.0)The fossils likewise could not have actually been photosynthetic, the scientists reported in their paper, since extremely little light would have permeated the water to their level. Chemical analysis exposed high levels of carbon in those rock layers– an indication that the wrinkles were formed by life.

Get the world’s most interesting discoveries provided directly to your inbox.

This life was most likely chemosynthetic, suggesting it got its energy through chain reactions instead of from sunshine, Martindale and her associates composed. Rather, these organisms would have lived off of sulfur or other substances. Today, chemosynthetic microbial mats form on continental racks, where undersea landslides and turbidites likewise take place.

Those landslides might have been important to the cycle that enabled the microorganisms to grow, the scientists discovered. Landslides toppling from the continent towards the deep ocean would have dragged down natural product, which would have disintegrated and produced substances such as methane or hydrogen sulfide– delicious treats for chemosynthetic life. In between landslides, microbial mats would have flourished. Often, they would have been gotten rid of by another particles circulation, however in other cases, their traces were protected.

The finding recommends that researchers need to broaden their look for indications of wrinkle structures from shallow developments to rocks that were initially formed in much deeper waters. This might lead them to more details about the earliest chemosynthetic organisms.

“Wrinkle structures,” Martindale stated, “are really important pieces of evidence in the early evolution of life.”

Martindale, R. C., Sinha, S., Stone, T. N., Fonville, T., Bodin, S., Krencker, F.-N., Girguis, P., Little, C. T. S., & & Kabiri, L. (2025 ). Chemosynthetic microbial neighborhoods formed wrinkle structures in ancient turbidites. Geology 54(2 ), 173– 178. https://doi.org/10.1130/g53617.1

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing author for Live Science, covering subjects varying from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and habits. She was formerly a senior author for Live Science however is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and routinely adds to Scientific American and The Monitor, the regular monthly publication of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie got a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science interaction from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You need to validate your show and tell name before commenting

Please logout and after that login once again, you will then be triggered to enter your screen name.

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.