Sunshine can trigger a particle to alter structure, and after that release heat later on.

The system works a bit like existing solar hot water heater, however with chemical heat storage.

Credit: Kypros

Heating represent almost half of the worldwide energy need, and two-thirds of that is fulfilled by burning nonrenewable fuel sources like gas, oil, and coal. Solar power is a possible option, however while we have actually ended up being fairly proficient at keeping solar electrical power in lithium-ion batteries, we’re not almost as proficient at saving heat.

To save heat for days, weeks, or months, you require to trap the energy in the bonds of a particle that can later on launch heat as needed. The technique to this specific chemistry issue is called molecular solar thermal (MOST) energy storage. While it has actually been the next huge thing for years, it never ever actually removed.

In a current Science paper, a group of scientists from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and UCLA show a development that may lastly make MOST energy storage efficient.

The DNA connection

In the past, MOST energy storage services have actually been afflicted by uninspired efficiency. The particles either didn’t keep sufficient energy, deteriorated too rapidly, or needed hazardous solvents that made them not practical. To discover a method around these problems, the group led by Han P. Nguyen, a chemist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, drew motivation from the hereditary damage triggered by sunburn. The concept was to save energy utilizing a response comparable to the one that enables UV light to damage DNA.

When you avoid on the beach too long, high-energy ultraviolet light can trigger surrounding bases in the DNA (thymine, the T in the hereditary code) to connect together. This forms a structure called a (6-4) sore. When that sore is exposed to a lot more UV light, it twists into an even complete stranger shape called a “Dewar” isomer. In biology, this is rather problem, as Dewar isomers trigger kinks in the DNA’s double-helix spiral that interrupt copying the DNA and can cause anomalies or cancer.

To counter this result, advancement formed a particular enzyme called photolyase to hunt (6-4) sores down and snap them back into their safe, steady types.

The scientists recognized that the Dewar isomer is basically a molecular battery. This snap-back result was precisely what Nguyen’s group was trying to find, because it launches a great deal of heat.

Rechargeable fuel

Molecular batteries, in concept, are incredibly proficient at keeping energy. Heating oil, probably the most popular molecular battery we utilize for heating, is basically ancient solar power kept in chemical bonds. Its energy density stands at around 40 Megajoules per kilo. To put that in viewpoint, Li-ion batteries normally load less than one MJ/kg. Among the issues with heating oil, however, is that it is single-use just– it gets charred when you utilize it. What Nguyen and her associates intended to attain with their DNA-inspired compound is basically a multiple-use fuel.

To do that, scientists manufactured a derivative of 2-pyrimidone, a chemical cousin of the thymine discovered in DNA. They crafted this particle to dependably fold into a Dewar isomer under sunshine and after that unfold on command. The outcome was a rechargeable fuel that might take in the energy when exposed to sunshine, release it when required, and go back to a “unwinded” state where it’s all set to be charged up once again.

Previous efforts at MOST systems have actually struggled to take on Li-ion batteries. Norbornadiene, among the best-studied prospects, peaks at around 0.97 MJ/kg. Another competitor, azaborinine, handles just 0.65 MJ/kg. They might be clinically intriguing, however they are not going to warm your home.

Nguyen’s pyrimidone-based system blew those numbers out of the water. The scientists accomplished an energy storage density of 1.65 MJ/kg– almost double the capability of Li-ion batteries and significantly greater than any previous MOST product.

Double rings

The factor for this dive in efficiency was what the group called compounded pressure.

When the pyrimidone particle soaks up light, it does not simply fold; it twists into a merged, bicyclic structure including 2 various four-membered rings: 1,2-dihydroazete and diazetidine. Four-membered rings are under tremendous structural stress. By merging them together, the scientists produced a particle that is desperate to snap back into its unwinded state.

Attaining high energy density on paper is something. Making it operate in the real life is another. A significant stopping working of previous MOST systems is that they are solids that require to be liquified in solvents like toluene or acetonitrile to work. Solvents are the opponent of energy density– by diluting your fuel to 10 percent concentration, for instance, you successfully cut your energy density by 90 percent. Any solvent pre-owned methods less fuel.

Nguyen’s group tackled this by developing a variation of their particle that is a liquid at space temperature level, so it does not require a solvent. This streamlined operations substantially, as the liquid fuel might be pumped through a solar battery to charge it up and save it in a tank.

Unlike numerous natural particles that dislike water, Nguyen’s system works with liquid environments. This implies if a pipeline leakages, you aren’t gushing hazardous fluids like toluene around your home. The scientists even showed that the particle might operate in water which its energy release was extreme sufficient to boil it.

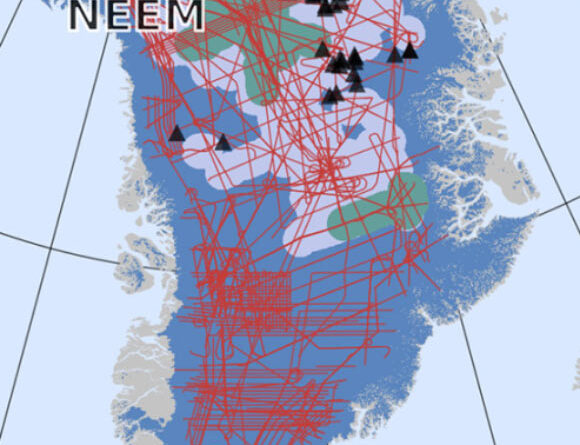

The MOST-based heater, the group states in their paper, would distribute this rechargeable fuel through panels on the roofing system to record the sun’s light and after that save it in the basement tank. The fuel from this tank would later on be pumped to a response chamber with an acid driver that sets off the energy release. Through a heat exchanger, this energy would warm up the water in the basic main heating system.

There’s a catch.

Searching for the leakage

The very first difficulty is the spectrum of light that puts energy in the Nguyen’s fuel. The Sun showers us in a broad spectrum of light, from infrared to ultraviolet. Preferably, a solar battery must utilize as much of this as possible, however the pyrimidone particles just take in light in the UV-A and UV-B variety, around 300-310 nm. That represents about 5 percent of the overall solar spectrum. The huge bulk of the Sun’s energy, the noticeable light and the infrared, passes right through Nguyen’s particles without charging them.

The 2nd issue is quantum yield. This is an elegant method of asking, “For every 100 photons that struck the particle, the number of really make it change to the Dewar isomer state?” For these pyrimidones, the response is a rather underwhelming number, in the single digits. Low quantum yield implies the fluid requires a longer direct exposure to sunshine to get a complete charge.

The scientists assume that the particle has a quick leakage, implying a non-radiative decay course where the fired up particle gets rid of the energy as heat right away rather of twisting into the storage type. Plugging that leakage is the next huge difficulty for the group.

The group in their experiments utilized an acid driver that was blended straight into the storage product. The group confesses that in a future closed-loop gadget, this would need a neutralization action– a response that removes the level of acidity after the heat is launched. Unless the response items can be cleansed away, this will lower the energy density of the system.

Still, in spite of the performance concerns, the stability of the Nguyen’s system looks appealing.

One of the most storage?

Among the most significant worries with chemical storage is thermal reversion– the fuel spontaneously releases since it got a little too warm in the tank. The Dewar isomers of the pyrimidones are extremely steady. The scientists computed a half-life of as much as 481 days at space temperature level for some derivatives. This suggests the fuel might be charged in the heat of July, and it would stay completely charged when you require to warm your home in January. The destruction figures likewise look good for a MOST energy storage. The group ran the system through 20 charge-discharge cycles with minimal decay.

The issue with separating the acid from the fuel might be resolved in a useful system by changing to a various driver. The researchers recommend in the paper that in this theoretical setup, the fuel would stream through an acid-functionalized strong surface area to launch heat, therefore getting rid of the requirement for neutralization later on.

Still, we’re rather far utilizing MOST systems for heating real homes. To arrive, we’re going to require particles that soak up much more of the light spectrum and transform to the triggered state with a greater performance. We’re simply not there.

Science, 2026. DOI: 10.1126/ science.aec6413

Jacek Krywko is a freelance science and innovation author who covers area expedition, expert system research study, computer technology, and all sorts of engineering wizardry.

89 Comments

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.