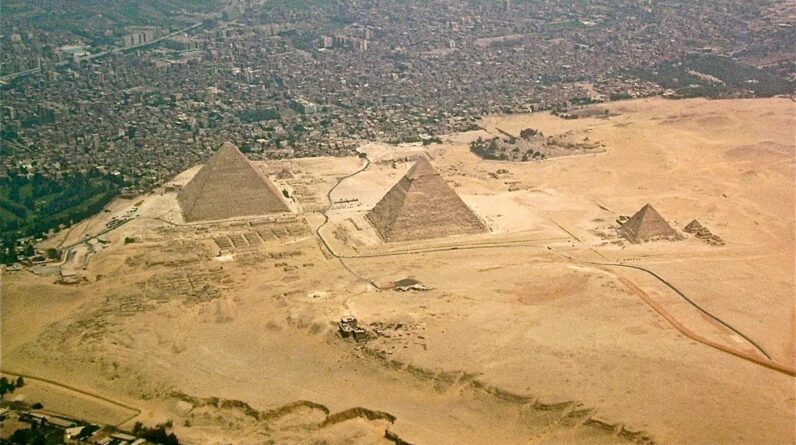

On a warm spring day in 2019, scientists tired into the earth underneath Cairo’s metropolitan streets. Simply over a kilometer away, the Great Pyramid of Giza sparkled on the horizon. Some 4,600 years previously, as workers built the Great Pyramid, the modern dig area lay on the sandy flooring of Khufu Harbor.

In this ancient harbor– the world’s earliest recognized port– scientists stated they’ve recognized the very first significant circumstances of human-induced metal contamination. The Giza necropolis is well-known for its pyramids and shriveled mummies, a brand-new research study released in Geology deals extraordinary proof of a mostly unheralded element of ancient Egyptian civilization: relentless, centuries-long metalworking.

The discovery clarifies life beyond the pharaonic and handsome elites of ancient Egypt, scientists stated. “We ‘d like to understand more about 95% of individuals instead of the elite,” stated Alain Vérona geochemist from France’s Aix-Marseille Université. His beliefs echo the ideas of Christophe Morhangea geoarchaeologist from the very same organization, who highlighted the significance of the sedimentary record in rebuilding historic stories.

Related: Long-lost branch of the Nile was ‘vital for constructing the pyramids,’ research study reveals

“The sediments are as essential as monoliths,” Morhange stated, highlighting the often-overlooked significance of the ground below our feet.

An unexpected history of contamination

The scientists utilized geochemical tracers to examine metalworking activities around ancient Khufu Harbor. Found along a now defunct branch of the Nile near the Giza Plateau, the harbor was important for transferring products and was the website of a significant copper toolmaking market. These tools, a few of which employees alloyed with arsenic for included resilience, consisted of blades, chisels, and drills to work products like limestone, wood, and fabrics. Scientists utilized inductively combined plasma– mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to determine levels of copper and arsenic, in addition to of aluminum, iron, and titanium, with 6 carbon-14 dates to develop a sequential structure.

The research study traced the beginning of metal contamination to around 3265 BCE, earlier than scientists prepared for. Contamination throughout this Predynastic duration recommends that human profession and metalworking at Giza started more than 200 years previously than formerly recorded.

Scientists have actually discovered direct proof of Predynastic civilization in only 13 tombs north of Giza, Morhange thinks the geoarchaeological record yields more ideas. With a lot concentrate on the pyramids and other burial places, he discussed, previous scientists may have neglected proof of the website’s earlier profession.

“You just discover what you are searching for,” he stated.

Scientists discovered that metal contamination peaked throughout late pyramid building and construction around 2500 BCE and continued till about 1000 BCE. “We discovered the earliest local metal contamination ever taped on the planet,” Véron stated. Levels of copper throughout this duration were “5 to 6 times greater than the natural background,” he continued, suggesting considerable regional commercial activity.

Andrew Shortlanda historical researcher from Cranfield University in the United Kingdom who was not associated with the research study, revealed issues about the proposed timeline. “I do not believe 6 dates suffices,” he stated, describing the variety of carbon-14 dates utilized.

Shortland acknowledged the research study’s more comprehensive conclusions about human-induced metal contamination at Giza.

Adjusting to ecological challenge

The research study offered more insight into how ancient Egyptians adjusted to ecological obstacles. As the Nile River declined and Khufu Harbor diminished, metalworking continued. As the Nile reached its most affordable level, around 2200 BCE– a duration spoiled by civil discontent and grim reports of cannibalism– metal contamination stayed high, recommending a durable facilities and labor force.

Véron discussed that the declining Nile at first provided chances for regional neighborhoods. Previous palynological research study— the research study of pollen grains– has actually revealed that farming activity rose as the subsiding Nile exposed fertile floodplains. Even as pyramid building and construction at Giza stopped, metalworking most likely continued to support growing pastoral activities.

Dominik Weissa geochemist from Imperial College London, discovered the research study “incredibly well done and thoroughly performed.” Keeping in mind the attraction of high-visibility websites like the Giza necropolis, he commemorated the brand-new link in between geochemistry and history and the possibility of clarifying the lives of daily ancient Egyptians.

“The chemical imprint of human activity stays, which can not be removed,” Véron stated.

This post was initially released on Eos.orgCheck out the initial short article

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.