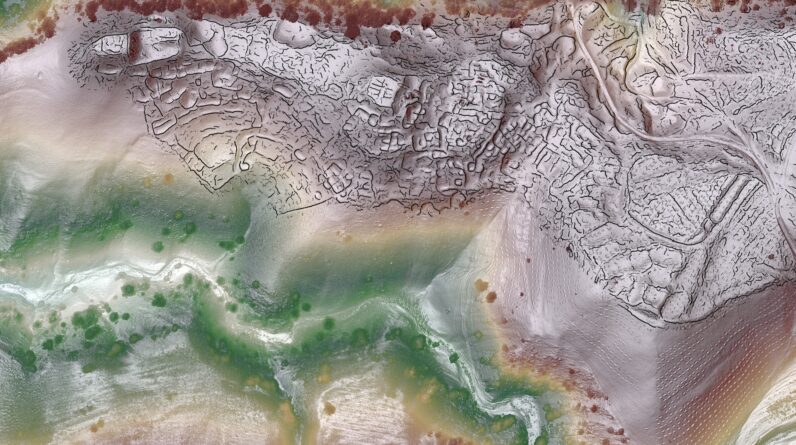

A lidar view of Tugunbulak, the website of an almost 300-acre middle ages city in Uzbekistan, with crest lines.

(Image credit: SAIElab/J. Berner/M. Frachetti )

Concealed in the towering mountains of Central Asia, along what has actually been called the Silk Roadarchaeologists are revealing 2 middle ages cities that might have bustled with residents a thousand years earlier.

A group initially observed among the lost cities in 2011 while treking the grassy mountains of eastern Uzbekistan looking for unknown history. The archaeologists travelled along the riverbed and identified burial websites along the method to the top of among the mountains. When there, a plateau dotted with weird mounds spread out before them. To the inexperienced eye, these mounds would not have actually appeared like much. “as archaeologists…, [we] recognize them as anthropogenic places, as places where people live,” states Farhod Maksudov of the National Center of Archaeology of the Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences.

The ground, too, was cluttered with countless pottery fragments. “We were kind of blown away,” states Michael Frachetti, an archaeologist at Washington University in St. Louis. He and Maksudov had actually remained in search of historical proof of nomadic cultures that grazed their herds on the mountain pastures. The scientists never ever anticipated to discover a 30-acre middle ages city in a reasonably unwelcoming environment around 7,000 feet above water level.

This website, called Tashbulak, after the location’s contemporary name, was just the start. While excavating in 2015, Frachetti met among the area’s only present occupants– a forestry inspector who deals with his household a couple of miles from Tashbulak. “He said, ‘In my backyard, I’ve seen ceramics like that,'” Frachetti remembers. The archaeologists drove to the forestry inspector’s plantation, where they discovered that his home rested on a familiar-looking mound.

“Sure enough, he’s living on a medieval citadel,” Frachetti states. From there, the scientists watched out at the landscape and saw much more mounds. “And we’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, this place is humongous,'” Frachetti includes.

This 2nd website, called Tugunbulak, is explained for the very first time in a research study released on October 23 in Nature. The scientists utilized remote-sensing innovation to map what they refer to as a vast, almost 300-acre middle ages city 3 miles from Tashbulak that was incorporated into the network of trade paths referred to as the Silk Road.

“It’s a pretty remarkable discovery,” states Zachary Silvia, an archaeologist at Brown University, who investigates this duration of Central Asian history and culture. (Silvia was not associated with the brand-new work, however he authored a commentary about it that was released in the very same problem of Nature.More excavations are required to validate Tugunbulak’s scope and density, “even if it turns out to be half the size [estimated here], that’s still a huge discovery,” he states– and one that might require a rethink of simply how stretching the Silk Road networks were.

Get the world’s most remarkable discoveries provided directly to your inbox.

On standard maps of the Silk Road, trade paths covering the Eurasian continent tend to prevent the mountains of Central Asia as much as possible. Low-lying cities such as Samarkand and Tashkent, which have the arable land and watering needed to support their busy populations, are viewed as having actually been the genuine locations for trade. On the other hand, the close-by Pamir mountains, where Tashbulak and Tugunbulak lie, are rugged and primarily nonarable since of their elevation. (Today less than 3 percent of the world’s population lives more than 2,000 meters, or about 6,500 feet, above water level.)

In spite of the minimal resources and freezing winter seasons, individuals did live at Tashbulak and Tugunbulak from the 8th to 11th centuries C.E., throughout the Middle Ages. Ultimately, whether gradually or simultaneously, the settlements were deserted and delegated the components. In the mountains, the landscape altered rapidly, and the remains of the cities were used down by disintegration and blanketed with sediment. A thousand years later on, what’s left are mounds, plateaus and ridges that are tough to map thoroughly with the naked eye.

A drone view of Tugunbulak. (Image credit: M. Frachetti)

To get an in-depth ordinary of the land, Frachetti and Maksudov geared up a drone with remote-sensing innovation called lidar(light detection and varying). Drones are firmly managed in Uzbekistan, however the scientists handled to get the needed authorizations to fly one at the website. A lidar scanner utilizes laser pulses to map the functions of land listed below. The innovation has actually been significantly utilized in archaeology– in the previous couple of years it has actually assisted discover a lost Maya city stretching below the jungle canopy in Guatemala.

At Tashbulak and Tugunbulak, the outcome was a relief map of the websites with inch-level information. With the aid of computer system algorithms, manual tracings and excavations, the scientists drew up subtle ridges that likely represented walls and other buried structures.

Related: 32 times lasers exposed covert forts and settlements from centuries ago

This technique has its constraints, Silvia states– specifically, it frequently shows up incorrect positives. It’s likewise difficult to validate which includes originated from which period without more excavation. Such work has actually been continuous at Tashbulak however has actually only simply started at Tugunbulak. (The scans and some excavation were finished in 2022, and Frachetti’s group went back to Tugunbulak this previous summertime to continue excavation. The scientists have yet to release their findings.) In the meantime, the lidar map of Tugunbulak appears to reveal a huge middle ages complex, total with a castle, structures, yards, plazas and paths, bounded by prepared walls. In addition to pottery, the group has actually excavated kilns, in addition to hints that employees in the city heated iron ores, Frachetti states.

Middle ages pottery excavated at Tugunbulak. (Image credit: M. Frachetti)

Metallurgy might be a crucial part of how the city might sustain itself at such a high elevation. The mountains are abundant in iron ore and have thick juniper forests, which might be burned to sustain the smelting procedure. The scientists have likewise exposed coins from throughout modern-day Uzbekistan, Maksudov states, recommending the city might have been a center for trade. It does not appear to have actually been strictly a mining settlement, either– at Tashbulak, a cemetery consists of the remains of females, senior individuals and babies.

“We have realized that this was a large urban center, which was integrated into the Silk Road network and dragged the Silk Road caravans toward mountains … because they had their own products to offer,” Maksudov states.

“There is a relationship between these cities” in the highlands and those in the lowlands, states Sanjyot Mehendale, an archaeologist and chair of the Tang Center for Silk Road Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. The trading networks of the Silk Road were “very, very fluid,” and societies when thought about peripheral and remote, such as those of Tashbulak and Tugunbulak, “were part of a network that stretched all across Eurasia,” she states. “You can no longer look at these areas and perceive them as remote or less developed.”

Mehendale ended up being included with the work at Tugunbulak after the lidar research study was finished, and she went to the website to excavate this previous summer season. She’s now most thinking about rebuilding what the city resembled throughout its life expectancy. Who were the residents? How did the population modification over seasons or centuries?

The responses to all these concerns are most likely there, buried in the sediment. The research study group, Silvia states, “has got a lifetime of work.”

This post was very first released at Scientific American© ScientificAmerican.comAll rights booked. Follow on TikTok and Instagram X and Facebook

Allison Parshallis an associate news editor atScientific Americanwho typically covers biology, health, innovation and physics. She modifies the publication’s Contributors column and weekly online Science Quizzes. As a multimedia reporter, Parshall adds toScientific American‘s podcastScience QuicklyHer work consists of a three-part miniseries on music-making expert system. Her work has actually likewise appeared inQuanta Magazineand Inverse. Parshall finished from New York University’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute with a master’s degree in science, health and ecological reporting. She has a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Georgetown University.

A lot of Popular

Learn more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.