Avoid to content

Marine Organizational Body Size (MOBS) database fills an important space in comprehending ocean biodiversity.

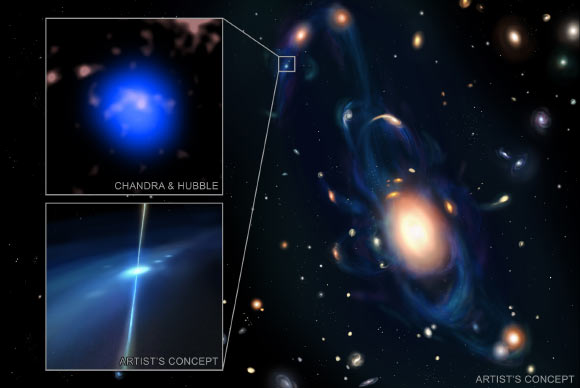

Craig McClain photographing a whale shark off the coast of Cancun, Mexico, to gather body size information.

Credit: Alistair Dove

Legend has it that physicist Ernest Rutherford as soon as dismissed all sciences besides physics as simple “stamp collecting.” (Whether he really stated it refers some dispute.) We now live in the details age, and researchers have actually discovered significant worth in collecting huge databases of info for massive analysis, allowing them to check out various kinds of concerns.

The current addition is the Marine Organizational Body Size (MOBS) database, an open-access resource that– as its name indicates– has actually gathered body size information for more than 85,000 marine animal types and counting, varying from tiny animals like zooplankton to the biggest whales. MOBS is currently allowing brand-new research study on the ocean’s biodiversity and worldwide community, according to a paper released in the journal Global Ecology and Biogeography. The database is now offered though GitHub and presently covers 40 percent of all explained marine animal types, with an objective of attaining 75 percent protection.

“We’ve really lacked that broader persecutive for a lot of ocean life,” marine ecologist Craig McClain of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette informed Ars. McClain is the lead developer of MOBS. “We know about evolution and ecology for mammals and birds especially, and to a lesser extent reptiles and amphibians. We just haven’t had these big collated body size data sets for the marine groups, especially the invertebrates.” The MOBS job is essentially building a “library of [marine] life.”

This in turn leads the way for research study on macroecology and macroevolution for marine animals. As McClain likes to state, “Body size isn’t just a number; it’s a key to how life works,” since that basic characteristic relates to “how a species moves, eats, survives, and evolves. What jellyfish do and their ecology is so much different than for a mammal that it makes you wonder how universal some of the [widely accepted] ‘rules’ really are.”

The ocean operates on size

McClain formally introduced MOBS as an enthusiasm job while on sabbatical in 2022 however he had actually been informally gathering information on body size for numerous marine groups for numerous years before that. He had a little set of information currently to kick off the task, integrating it all into a single big database with a constant set format and design.

Craig McClain holding a huge isopod(Bathynomus giganteusamong the deep sea’s most renowned shellfishes

Credit: Craig McClain

“One of the things that had prevented me from doing this before was the taxonomy issue,” stated McClain. “Say you wanted to get the body size for all [species] of octopuses. That was not something that was very well known unless some taxonomist happened to publish [that data]. And that data was likely not up-to-date because new species are [constantly] being described.”

In the last 5 to 10 years, the World Register of Marine Species(WoRMS )was developed with the goal of cataloging all marine life, with taxonomy specialists appointed to particular groups to figure out legitimate brand-new types, which are then included to the information set with a particular mathematical code. McClain connected his own dataset to that exact same code, making it rather simple to upgrade MOBS as brand-new types are contributed to WoRMS. McClain and his group were likewise able to collect body size information from numerous museum collections.

The MOBS database concentrates on body length (a direct measurement) rather than body mass. “Almost every taxonomic description of a new species has some sort of linear measurement,” stated McClain. “For most organisms, it’s a length, maybe a width, and if you’re really lucky you might get a height. It’s very rare for anything to be weighed unless it’s an objective of the study. So that data simply doesn’t exist.”

While all mammals typically have comparable density, “If you compare the density of a sea slug, a nudibranch, versus a jellyfish, even though they have the same masses, their carbon contents are much different,” he stated. “And a one-meter worm that’s a cylinder and a one-meter sea urchin that’s a sphere are fundamentally different weights and different kinds of organisms.” One option for the latter is to transform to volume to represent shape distinctions. Length-to-weight ratios can likewise vary considerably for various marine animal groups. That’s why McClain wants to put together a different database for length-to-weight conversions.

While body size may appear to be a fairly simple measurement to take, compared to something physiological like metabolic rate, when it pertains to marine animals there can be special obstacles. McClain remembered dealing with a job to determine the length of whale sharks in the wild. “You can’t just swim up and extend a tape measure down the length of a whale shark,” he stated.

The service was undoubtedly complicated, however it worked. “We would swim up to the shark, shoot a couple of laser dots on their side at known widths, and take pictures. We knew that the distance between their last gill and the dorsal fin scaled with total body length, so that’s how we figured it out.” By contrast, determining the lengths of submillimeter organisms has actually generally included taking numerous images under a microscopic lense and carrying out image analysis.

Researchers are currently utilizing MOBS to study things like whether the size-related patterns in descriptions of types in biodiversity databases may show longstanding predispositions. It likewise supplies McClain and his group with a feasible research study focus at a time when federal financing for clinical research study is dealing with an existential crisis.

“The other work I do, deep sea research, is very expensive and requires grant funding,” stated McClain. “The great thing about this project is that it only really requires me and a laptop and some other people and their laptops. It may be over the next few years, while there’s no funding to do any other field or lab science, that this may be our main focus. At the end of the day, [MOBS] is going to require lots of people approaching this from a lot of different ways to get great coverage across all these different groups.”

DOI: Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2025. 10.1111/ geb.70062 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior author at Ars Technica with a specific concentrate on where science satisfies culture, covering whatever from physics and associated interdisciplinary subjects to her preferred movies and television series. Jennifer resides in Baltimore with her partner, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their 2 felines, Ariel and Caliban.

12 Comments

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.