Shadrack Byfield lost his left arm in the War of 1812; his life clarifies post-war re-integration.

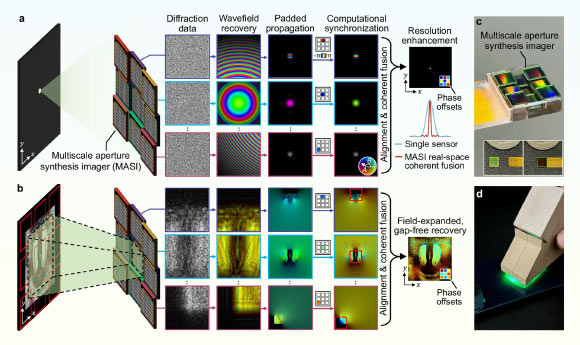

Star Chris McKay playing Shadrack Byfield (center) in the 2011 PBS documentary The War of 1812.

Credit: Tom Fournier

History enthusiasts are no doubt acquainted with the story of Shadrack Byfield, a rank-and-file British redcoat who battled throughout the War of 1812 and lost his left arm to a musket ball for his difficulty. Byfield has actually been included in many popular histories– consisting of a kids’s book and a 2011 PBS documentary– as a shining example of a handicapped soldier’s stoic determination. A recently found narrative that Byfield released in his later years is making complex that idealized photo of his post-military life, according to a brand-new paper released in the Journal of British Studies.

Historian Eamonn O’Keeffe of Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John’s, Canada, has actually been a Byfield fan since he checked out the 1985 kids’s book, Redcoatby Gregory Sass. His interest grew when he was operating at Fort York, a War of 1812-era fort and museum, in Toronto. “There are lots of memoirs composed by British rank-and-file veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, however just a handful from the War of 1812, which was much smaller sized in scale,” O’Keeffe informed Ars. “Byfield’s autobiography appeared to use a genuine, ground-level view of the combating in North America, assisting us look beyond the generals and political leaders and face the ramifications of this dispute for common individuals.

Born in 1789 in Wiltshire’s Bradford-on-Avon residential areas, Byfield’s moms and dads meant him to follow in his weaver dad’s steps. He employed in the county militia when he turned 18 rather, signing up with the routine army the list below year. When the War of 1812 broke out, Byfield was stationed at Fort George along the Niagara River, taking part in the effective siege of Fort Detroit. At the Battle of Frenchtown in January 1813, he was shot in the neck, however he recuperated adequately to sign up with the projects versus Fort Meigs and Fort Stephenson in Ohio.

After the British were beat at the Battle of Thames later on that year, he left into the woods with native warriors, in spite of his issues that they indicated to eliminate him. They did not, and Byfield ultimately rejoined other British fugitives and made his method back to the British lines. He was among 15 out of 110 soldiers in his light business still alive after 18 months of combating.

His luck ran out in July 1814. While participated in a skirmish at Conjocta Creek, a musket ball tore through his left lower arm. Surgeons were required to cut off after gangrene set in– a treatment that was carried out without anesthesia. Byfield explained the operation as “laborious and agonizing” in A Narrative of a Light Company Soldier’s Servicethe narrative he released in 1840, including, “I was made it possible for to bear it quite well.”

Byfield notoriously ended up being incensed when he found his severed limb had actually been tossed into a dung load with other amputated body parts. He obtained his lower arm and demanded providing it a correct burial in a makeshift casket he constructed himself. Due to his injury, Byfield’s military profession was over, and he went back to England. While he was offered an army pension, the amount (9 cent daily) was insufficient to support the veteran’s growing household.

Byfield could not use up his daddy’s weaving trade since it took 2 hands to run a loom. According to his 1840 Narrativehe had a dream one night of an “instrument” that would allow him to work a loom with simply one arm, which he effectively constructed with the assistance of a regional blacksmith. He discovered work spinning thread at a fabric mill and weaving it into ended up fabric, enhancing that trade by working as a wheelchair attendant at a day spa in Bath, to name a few chores. He later on discovered a coach in Colonel William Napier, a recognized veteran and military historian who scheduled a boost in Byfield’s pension, in addition to discovering a publisher for the Narrative

A moving narrative

Byfield’s 1840 narrative ended up being a much-cited source for historians of the War of 1812 considering that it used an individual point of view on those occasions from a rank-and-file British soldier. Historians had long presumed that Byfield passed away around 1850.Throughout his research study, O’Keeffe found a 2nd Byfield narrative in the collection of the Western Reserve Historical Society, released in 1851, entitled History and Conversion of a British SoldierO’Keeffe thinks this to be the only enduring copy of the 1851 narrative.

“I rapidly saw that [Byfield] appeared in British census records past the c. 1850 date at which he was expected to have actually passed away, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia entry on Byfield and other sources,” stated O’Keeffe. “This disparity was my very first sign that there may be more to find on Byfield, and each time I went back to the topic I kept discovering more info.” Byfield really passed away in January 1874 at 84 years of ages. While historians had actually likewise presumed that Byfield was functionally illiterate, O’Keeffe discovered a draft manuscript of the 1840 narrative in Byfield’s handwriting, recommending the soldier had actually obtained those abilities after the war.

“My preliminary interest was triggered by the wartime narrative I currently learnt about, however I was significantly captivated by his later life, and what it might inform us about the experiences of veterans in basic,” stated O’Keeffe. “In the majority of history books, British redcoats take spotlight for the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of the Waterloo, however then rapidly disappear from view; no doubt this holds true for veterans of many if not all wars. Military memoirs of the duration tend to motivate this vibrant by ending the story at demobilization, presuming that readers would not have an interest in the civilian experiences of their authors. Byfield’s extremely well-documented life assists bring the procedure of reintegration, of restoring one’s life after war and disastrous injury, into sharper focus, and highlights the existence of war veterans in 19th-century British society.”

According to O’Keeffe, Byfield painted a much less rosy image of his post-military life in the 1851 narrative, stating his battles with hardship and remaining rheumatic discomfort in his left stump. (“Oftentimes I was unable to raise my hand to my head, nor a teacup to my mouth,” the previous soldier composed.) When fabric mills began closing, he transferred his household to Gloucestershire and eked out a living as a tollkeeper and by offering copies of his earlier Narrative for a shilling. He confessed to taking lack without leave throughout his war service and taking part in ransacking explorations. The later narrative likewise states Byfield’s spiritual awakening and growing spiritual faith.

Byfield embraced really various narrative styles in his 1840 and 1851 memoirs. “In the 1840 story, Byfield looked for to impress rich customers by providing himself as a devoted soldier and deserving veteran,” stated O’Keeffe. “The 1851 narrative, by contrast, was a spiritual redemption story, with Byfield tracing his development from defiant sinner to devout and repentant Christian. In the 1851 narrative, the veteran likewise harps on durations of insolvency, disease, and joblessness after going back to England, whereas in his earlier narrative he explained keeping his household ‘easily’ with his weaving prosthesis for almost twenty years.”

Byfield’s luck appeared to alter for the much better when the Duke of Beaufort ended up being a client, very first employing the veteran as a garden enthusiast on the duke’s Badminton estate. Byfield grumbled in his 1851 account that the estate steward declined to pay him complete salaries due to the fact that he was one-handed, firmly insisting, “I never ever saw the male that would take on me with one arm.”

Ultimately, Byfield leveraged his connection to the duke to be called caretaker of a 100-foot tower monolith to Lord Edward Somerset that was integrated in the Gloucestershire town of Hawkesbury Upton in 1845. This included a keeper’s home, and the tasks were light: Byfield kept the tower, offered keepsake brochures, and invited any tourists every day other than Sundays.

Sadly, Byfield ended up being involved in a fight over control of the town’s Particular Baptist chapel; some challenged the teaching and conduct of the minister, John Osborne, while others, like Byfield, safeguarded him. There were suits, arson, vandalism, and a charge of public drunkenness versus Byfield, which he emphatically rejected. Whatever capped in an “unholy riot” in the chapel, throughout which Byfield was implicated of beginning the battle by “pressing about” and slashing somebody’s eye and confront with his prosthetic iron hook. Every rioter was acquitted, however the event expense Byfield his soft caretaker task in 1853.

Byfield later on returned to his home town, Bradford-on-Avon, and wed a widow after his very first better half passed away. He kept petitioning for additional boosts to his pension, to no obtain, and began marketing a 3rd narrative in 1867 entitled The Forlorn HopeNo copies have actually made it through, per O’Keeffe, however it did gather protection in a regional paper, which explained the account as relating “the Christian experience of this Wiltshire hero and the excellent persecutions and trials he has actually travelled through.”

“Years earlier, I would have identified the veteran as somebody who was amazingly phlegmatic about what took place to him,” stated O’Keeffe. “Byfield’s description of the amputation stumbles upon as incredibly unemotional to contemporary readers, and after that he provides himself at the end of the very first narrative as having actually thought up the prosthetic that permitted him to go back to his civilian trade and live gladly ever after, basically.”

As he studied Byfield’s works more carefully, “It ended up being clear that the procedure of reintegration was far less smooth than this variation of occasions would recommend, and that Byfield’s time in the army formed the rest of his life in extensive methods,” stated O’Keeffe. “The truth that Byfield’s child picked to put her daddy’s military rank and routine in the ‘profession’ column on his death certificate, instead of noting any of the other tasks the veteran had actually kept in the 6 years considering that his amputation, is the most significant testament of this, I believe.”

Journal of British Studies, 2025. DOI: 10.1017/ jbr.2025.10169 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior author at Ars Technica with a specific concentrate on where science fulfills culture, covering whatever from physics and associated interdisciplinary subjects to her preferred movies and television series. Jennifer resides in Baltimore with her partner, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their 2 felines, Ariel and Caliban.

24 Comments

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.