(Image credit: Universal History Archive through Getty Images)

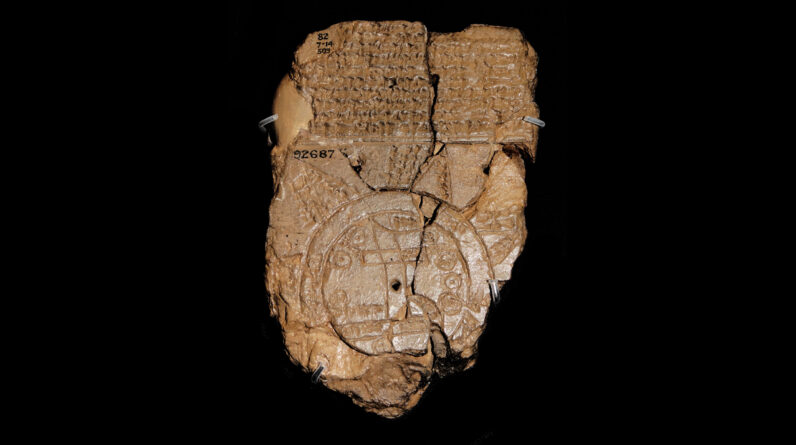

Call: Babylonian Map of the World (“Imago Mundi” in Latin)

What it is: A clay tablet engraved with the earliest recognized map of the ancient world

Where it is from: Abu Habba (Sippar), an ancient Babylonian city in what is now Iraq

When it was made: Roughly the 6th century B.C.

Related: Ancient Egyptian head cones: Mysterious headgear that might be associated with sensuality and fertility routines

What it informs us about the past:

This tablet, which portrays how Babylonians viewed the world countless years earlier, is peppered with information that provide insight into an earlier time. The ancient world is revealed as a particular disc, which is surrounded by a ring of water called the Bitter River. At the world’s center sits the Euphrates River and the ancient Mesopotamian city of BabylonLabels composed in cuneiform, an ancient text, keep in mind each place on the map, according to The British Museum

Remarkably, cartographers might have utilized some innovative license. “Babylon” is marked on just one end of the Euphrates, even though it inhabited both banks for many of its history.

MORE ASTONISHING ARTIFACTS

Above the map is a block of text explaining the production of the world by Marduk, the chief god of Babylonia. The description names more than a lots animals– consisting of a mountain goat, lion, leopard, hyena and wolf– in addition to a number of significant rulers, such as Utnapishtim, a king who endured an legendary flood

On the back of the map is more text explaining 8 removed areas, referred to as nagu, each with a brief description.

The tablet, which determines 4.8 inches high by 3.2 inches broad (12.2 by 8.2 centimeters), becomes part of The British Museum’s irreversible collection.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.