Avoid to content

The Maya were landscape engineers on a grand scale, even when it concerned fishing.

The Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary is a biodiverse wetland in what’s now Belize– however the precursors of the Maya turned it into an industrial-scale fishing operation.

Credit: Fernando Flores

On the eve of the increase of the Maya civilization, individuals residing in what’s now Belize turned an entire wetland into a huge network of fish traps huge enough to feed countless individuals.

We currently understand that the Maya turned swamps into breadbaskets by draining pipes and developing raised blocks of land for maize fields. A current study of a wetland in what’s now Belize recommends that the increase of the Maya civilization was sustained not simply by maize however by heaps of fish every year. University of New Hampshire archaeologist Eleanor Harrison-Buck and her coworkers just recently mapped a network of channels and ponds for trapping fish, developed right before the Maya civilization increased to prominence.

Fish in a barrel

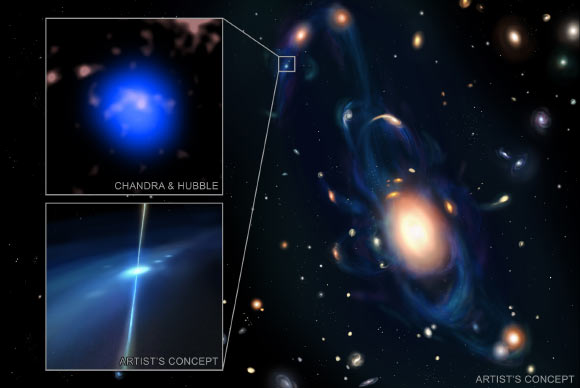

Harrison-Buck and her fellow archeologists utilized drones and Google Earth information to map 108 kilometers of ancient channels that zigzag throughout 42 square kilometers of wetland in Belize’s Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary. The outcome is a network of channels and ponds that looks incredibly like the fish traps discovered further south in Bolivia, developed a number of centuries after the ones at Crooked Tree. Radiocarbon dating of product buried in the bottom of one channel recommends that the network has actually been around for a minimum of 4,000 years.

If Harrison-Buck and her associates are right, the channels, together with a series of ponds, are a system for trapping fish by funneling declining floodwaters into the ponds. In the ponds, collecting the fish would have been simple– much like spearing fish in a barrel (or a little pond).

The Crooked Tree Wildlife Sanctuary is a vast marshy meadow dotted with lakes and cut by streams. Throughout the damp season, floods immerse the marshes and fish collect to generate, as they’ve provided for countless years (a minimum of). As the water declines and the dry season sets in, pulling back fish escape down the zigzag channels went into the landscape, right into the ponds. And as soon as the water levels drop even further, the fish in the ponds have no other way to get away.

Harrison-Buck and her coworkers computed that at its peak, the system might have produced adequate fish each year to feed around 15,000 individuals. That’s based upon modern-day quotes of the number of kgs of fish individuals consume every year, integrated with measurements of the number of kgs of fish individuals in Zambia harvest with comparable traps. Naturally, individuals at Crooked Tree would require to maintain the fish in some way, most likely by salting, drying, or smoking them.

“Fisheries were more than efficient in supporting year-round sedentarism and the introduction of complicated society attribute of Pre-Columbian Maya civilization in this location,” compose Harrison-Buck and her associates.

When we think of the Maya economy, we think about canal networks and dumped or terraced fields. In simply one spot of what’s now Guatemala, a lidar study exposed that Maya farmers drained pipes countless acres of swampy wetland and developed raised fields for maize, crossed by a grid of watering canals. To feed the ancient city of Holmul, the Maya turned an overload into a breadbasket. At least some of their precursors might have made it huge on fish, not grain. The typical function, however, is an outright absence of any chill whatsoever when it pertained to re-engineering entire landscapes to produce food.

This Google Earth image reveals the location including the ancient fishery.

Facilities developed to last and last

From the ground, the channels that funneled fish into neighboring ponds are almost unnoticeable today. From above, specifically throughout the dry season, they stand in plain contrast to the land around them, since plants grows abundant and green in the damp soil at the base of the channels, even while whatever around it dries up. That made aerial photography the ideal method to map them.

In 3 of the channels, Harrison-Buck and her coworkers took samples of peat, which would as soon as have actually depended on the bottom of the newly dug passage, for radiocarbon screening. The outcomes recommend that the channel had actually existed considering that a minimum of 2000 BCE. That’s about 200 years before the start of the Formative Period, which marks the start of the increase of Maya civilization. (The Formative Period is likewise called the Preclassic Period; the duration prior to this is called the Archaic, so the channels were constructed really late in the Archaic Period.)

The Maya obviously kept utilizing the fish-trapping system even as their civilization grew and combined into big city. Harrison-Buck and her associates discovered littles Preclassic Maya pottery in a few of the lower layers of sediment that had actually filled the channels, and other archaeologists have actually excavated as soon as largely inhabited Maya neighborhoods along the coast of the Western Lagoon.

There’s no indication that the Preclassic Maya did much to preserve the system of channels and ponds. Today, the majority of the channels have actually completed with sediment, brought in by floodwaters, making them simply subtle, curved dips in the ground, about 20 centimeters deep and 15 to 20 meters broad.

Even now, the ancient channel system still works. “While these functions have actually completed rather for many years, residents notify us that the ponds still focus fish throughout the dry season today,” compose Harrison-Buck and her associates.

Science Advances, 2017. DOI: 10.1126/ sciadv.adq1444 (About DOIs).

Kiona is a freelance science reporter and resident archaeology geek at Ars Technica.

46 Comments

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.