fighting the brackish water

Some state it’s a pricey pipeline dream; others state it’s part of the future.

Ralph Loya was quite sure he was going to lose the corn. His farm had actually been blistered by El Paso’s hottest-ever June and second-hottest August; the West Texas county saw 53 days skyrocket over 100 ° Fahrenheit in the summer season of 2024. The area was likewise experiencing a continuous dry spell, which indicated that crops on Loya’s eight-plus acres of melons, okra, cucumbers, and other fruit and vegetables needed to be watered regularly than regular.

Loya had actually been watering his corn with rather salted, or brackish, water pumped from his well, as much as the salt-sensitive crop might endure. It wasn’t enough, and the community water was pricey; he was utilizing it in small amounts, and the corn ears were desiccating where they stood.

Making sure the survival of farming under a progressively irregular environment is approaching a crisis in the sere and sweltering Western and Southwestern United States, a location that provides much of our beef and dairy, alfalfa, tree nuts, and produce. Competing with insufficient water to support their plants and animals, farmers have actually tilled under crops, took out trees, fallowed fields, and sold herds. They’ve likewise utilized drip watering to inject smaller sized dosages of water more detailed to a plant’s roots and set up sensing units in soil that inform more exactly when and just how much to water.

In the last 5 years, scientists have actually started to puzzle out how brackish water, pulled from underground aquifers, may be de-salted inexpensively enough to provide farmers another water strength tool. Loya’s residential or commercial property, which draws its somewhat salted water from the Hueco Bolson aquifer, will end up being a pilot website to evaluate how effectively desalinated groundwater can be utilized to grow crops in otherwise water-scarce locations.

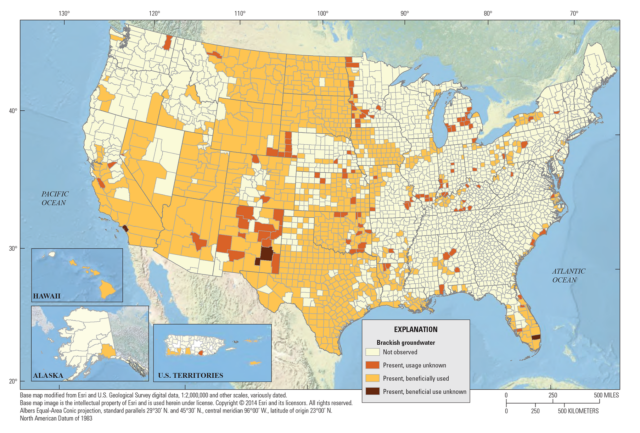

Desalination renders salted water less so. It’s typically used to water drawn from the ocean, usually in dry lands with couple of choices; some Gulf, African, and island nations rely greatly or completely on desalinated seawater. Inland desalination occurs far from coasts, with aquifer waters that are brackish– including in between 1,000 and 10,000 milligrams of salt per liter, versus around 35,000 milligrams per liter for seawater. Texas has more than 3 lots centralized brackish groundwater desalination plants, California more than 20.

Such innovation has actually long been thought about too expensive for farming. Some professionals still believe it’s a pipeline dream. “We see it as a good service that’s proper in some contexts, however for farming, it’s tough to validate, honestly,” states Brad Franklin, a farming and ecological economic expert at the general public Policy Institute of California. Desalting an acre-foot (nearly 326,000 gallons) of brackish groundwater for crops now costs about $800, while farmers can pay a lot less– just $3 an acre-foot for some senior rights holders in some locations– for fresh community water. As an outcome, desalination has actually mainly been booked to make liquid that’s suitable for individuals to consume. In some circumstances, too, inland desalination can be ecologically dangerous, threatening close-by plants and animals and lowering stream circulations.

The United States Bureau of Reclamation, along with a research study operation called the National Alliance for Water Innovation (NAWI) that’s been approved $185 million from the Department of Energy, have actually just recently invested in jobs that might turn that paradigm on its head. Acknowledging the immediate requirement for fresh water for farms– which in the United States are primarily inland– integrated with the sufficient if salted water underneath our feet, these entities have actually moneyed jobs that might assist advance little, decentralized desalination systems that can be put right on farms where they’re required. Loya’s is among them.

United States farms take in over 83 million acre-feet (more than 27 trillion gallons) of watering water every year– the 2nd most water-intensive market in the nation, after thermoelectric power. Not all aquifers are brackish, however the majority of that are exist in the nation’s West, and they’re normally more saline the much deeper you dig. With fresh water all over worldwide ending up being saltier due to human activity, “we need to fix inland desal for ag … in order to grow as much food as we require,” states Susan Amrose, a research study researcher at MIT who studies inland desalination in the Middle East and North Africa.

That implies decreasing energy and other functional expenses, making systems basic for farmers to run; and determining how to slash recurring salt water, which needs disposal and is thought about the procedure’s” Achilles ‘heel,” according to one scientist.

The last half-decade of clinical tinkering is now yielding concrete outcomes, states Peter Fiske, NAWI’s executive director. “We believe we have a clear line of vision for agricultural-quality water.”

Swallowing the high expense

Fiske thinks farm-based mini-plants can be cost-efficient for producing high-value crops like broccoli, berries, and nuts, a few of which require a great deal of watering. That $800 per acre-foot has actually been attained by cutting energy usage, decreasing salt water, and changing particular parts and products. It’s still pricey however perhaps worth it for a farmer growing almonds or pistachios in California– rather than farmers growing lesser-value product crops like wheat and soybeans, for whom desalination will likely never ever show budget-friendly. As a nut farmer, “I would register to 800 dollars per acre-foot of water till the cows get back,” Fiske states.

Loya’s pilot is being developed with Bureau of Reclamation financing and will utilize a typical procedure called reverse osmosis. Pressure presses salted water through a semi-permeable membrane; fresh water comes out the opposite, leaving salts behind as focused salt water. Loya figures he can make great cash utilizing desalinated water to grow not simply picky corn, however even fussier grapes he may be able to cost a premium to regional wineries.

Such a small system shares a few of the issues of its massive cousins– primarily, salt water disposal. El Paso, for instance, boasts the greatest inland desalination plant on the planet, that makes 27.5 million gallons of fresh drinking water a day. There, every gallon of brackish water gets divided into 2 streams: fresh water and recurring salt water, at a ratio of 83 percent to 17 percent. Considering that there’s no ocean to discard salt water into, just like seawater desalination, this plant injects it into deep, permeable rock developments– a procedure too costly and complex for farmers.

What if desalination could develop 90 or 95 percent fresh water and 5 to 10 percent salt water? What if you could get 100 percent fresh water, with simply a bag of dry salts remaining? Dealing with those solids is a lot more secure and simpler, “since super-salty water salt water is actually destructive … so you need to truck it around in stainless-steel trucks,” Fiske states.

What if those salts could be broken into elements– lithium, vital for batteries; magnesium, utilized to produce alloys; plaster, turned into drywall; as well as gold, platinum, and other rare-earth aspects that can be offered to producers? Currently, the El Paso plant takes part in “mining” plaster and hydrochloric acid for commercial clients.

Loya’s salt water will be piped into an evaporation pond. Ultimately, he’ll need to pay to land fill the dried-out solids, states Quantum Wei, creator and CEO of Harmony Desalting, which is developing Loya’s plant. There are other costs: drilling a well (Loya, fortunately, currently has one to serve the task); developing the physical plant; and providing the electrical power to pump water up day after day. These are bitter monetary tablets for a farmer. “We’re not getting abundant; by no methods,” Loya states.

More expense originates from the desalination itself. The energy required for reverse osmosis is a lot, and the saltier the water, the greater the requirement. In addition, the membranes that capture salt are gossamer-thin, and all that pressure damages them; they likewise get gunked up and require to be treated with chemicals.

Reverse osmosis provides another issue for farmers. It does not simply eliminate salt ions from water however the ions of helpful minerals, too, such as calcium, magnesium and sulfate. According to Amrose, this suggests farmers need to include fertilizer or mix in pretreated water to change vital ions that the procedure got.

To prevent such difficulties, one NAWI-funded group is explore ultra-high-pressure membranes, made out of stiffer plastic, that can endure a much more difficult push. The outcomes up until now look “rather motivating,” Fiske states. Another is checking out a system in which a chemical solvent dropped into water isolates the salt without a membrane, like the polymer inside a diaper takes in urine. The solvent, in this case the typical food-processing substance dimethyl ether, would be utilized over and over to prevent possibly harmful waste. It has actually shown low-cost enough to be thought about for farming usage.

Amrose is checking a system that utilizes electrodialysis rather of reverse osmosis. This sends out a consistent rise of voltage throughout water to pull salt ions through a rotating stack of favorably charged and adversely charged membranes. Discusses Amrose, “You get the unfavorable ions approaching their particular electrode till they can’t go through the membranes and get stuck,” and the very same occurs with the favorable ions. The procedure gets much greater fresh water healing in little systems than reverse osmosis, and is two times as energy effective at lower salinities. The membranes last longer, too– 10 years versus 3 to 5 years, Amrose states– and can permit necessary minerals to travel through.

Data-based style

At Loya’s farm, Wei paces the home on a sweltering summertime early morning with a regional engineering business he’s tapped to create the salt water storage pond. Loya is distressed that the pond be as little as possible to keep arable land in production; Wei is more worried that it be huge and deep enough. To factor this, he’ll take a look at typical weather considering that 1954 in addition to worst-case information from the last 25 years referring to month-to-month evaporation and rains rates. He’ll likewise divide the area into 2 areas so one can be cleaned up while the other remains in usage. Loya’s pond will likely be one-tenth of an acre, dug 3 to 6 feet deep.

The desalination plant will match reverse osmosis membranes with a “batch” procedure, pressing water through numerous times rather of as soon as and slowly amping up the pressure. Routine reverse osmosis is energy-intensive due to the fact that it continuously uses the greatest pressures, Wei states, however Harmony’s procedure conserves energy by utilizing lower pressures to begin with. A backwash in between cycles avoids scaling by liquifying mineral crystals and cleaning them away. “You truly get the advantage of the farmer not needing to handle dosing chemicals or changing membranes,” Wei states. “Our objective is to make it as pain-free as possible.”

Another Harmony development focuses remaining salt water by running it through a nanofiltration membrane in their batch system; such membranes are generally utilized to pretreat water to cut down on scaling or to recuperate minerals, however Wei thinks his system is the very first to integrate them with batch reverse osmosis. That’s what’s actually going to slash salt water volumes,” he states. The entire system will be connected to photovoltaic panels, keeping Loya’s energy off-grid and basically totally free. If all goes to strategy, the system will be functional by early 2025 and produce 7 gallons of fresh water a minute throughout the greatest sun of the day, with an objective of 90 to 95 percent fresh water healing. Any water not right away utilized for watering will be kept in a tank.

Expanding the research study

Ninety-eight miles north of Loya’s farm, along a dead flat and constantly beige stretch of roadway that skirts the White Sands Missile Range, more desalination jobs burble away at the Brackish Groundwater National Desalination Research Facility in Alamogordo, New Mexico. The center, run by the Bureau of Reclamation, uses researchers a laboratory and 4 wells of varying salinities to fiddle with.

On some dry acreage at the foot of the Sacramento Mountains, a longstanding farming pilot job bakes in ruthless sunshine. After some preemptive words about the 3 salt water ponds on the home–” They have an intriguing odor, in between zoo and ocean”– center supervisor Malynda Cappelle drives a golf cart filled with visitors past solar ranges and water tanks to a fenced-in parcel of dust and plants. Here, given that 2019, a group from the University of North Texas, New Mexico State University, and Colorado State University has actually checked sunflowers, fava beans, and, presently, 16 plots of pinto beans. Some plots are bare dirt; others are topped with garden compost that increases nutrients, keeps soil wet, and offers a salt barrier. Some plots are drip-irrigated with brackish water directly from a well; some get a desalinated/brackish water mix.

Eyeballing the plots even from a range, the plants in the freshest-water plots look big and healthy. Those with garden compost are nearly as energetic, even when watered with brackish water. This might have substantial ramifications for cash-conscious farmers. “Maybe we do a lower level of desalination, more mixing, and this will lower the expense,” states Cappelle.

Pei Xu has actually been co-investigator on this job because its start. She’s likewise the progenitor of a NAWI-funded pilot at the El Paso desalination plant. Later on in the day, in a high-ceilinged area beside the plant’s treatment space, she displays its substantial bits. Like Amrose’s system, hers utilizes electrodialysis. In this circumstances, however, Xu is intending to squeeze a little bit of extra fresh– a minimum of freshish– water from the plant’s remaining salt water. With appropriately low levels of salinity, the plant might pipeline it to farmers through the county’s existing canal system, turning a waste item into an important resource.

Xu’s pinto bean and El Paso work, and Amrose’s in the Middle East, are all pertinent to Harmony’s pilot and future tasks. “Ideally we can enhance desalination to the point where it’s an alternative which is seriously thought about,” Wei states. “But more significantly, I believe our function now and in the future is as water stewards– to deal with each farm to comprehend their circumstance and after that to suggest their finest course forward … whether desalting is included.”

As water deficiency ends up being ever more intense, desalination advances will assist farming just so much; even scientists who’ve dedicated years to fixing its obstacles state it’s no remedy. “What we’re attempting to do is provide as much water as inexpensively as possible, however that does not truly motivate wise water usage,” states NAWI’s Fiske. “In some cases, it motivates even the reverse. Why are we growing alfalfa in the middle of the desert?”

Franklin, of the California policy institute, highlights another extreme: Twenty-one of the state’s groundwater basins are currently seriously diminished, some due to farming overdrafting. Pumping brackish aquifers for desalination might intensify ecological threats.

There are a selection of steps, state scientists, that farmers themselves need to take in order to make it through, with rainwater capture and the repairing of leaking facilities at the top of the list. “Desalination is not the very best, just, or initially service,” Wei states. He thinks that when utilized sensibly in tandem with other clever partial repairs, it might avoid some of the worst water-related disasters for our food system.

Knowable Magazine checks out the real-world significance of academic resolve a journalistic lens.

61 Comments

Learn more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.