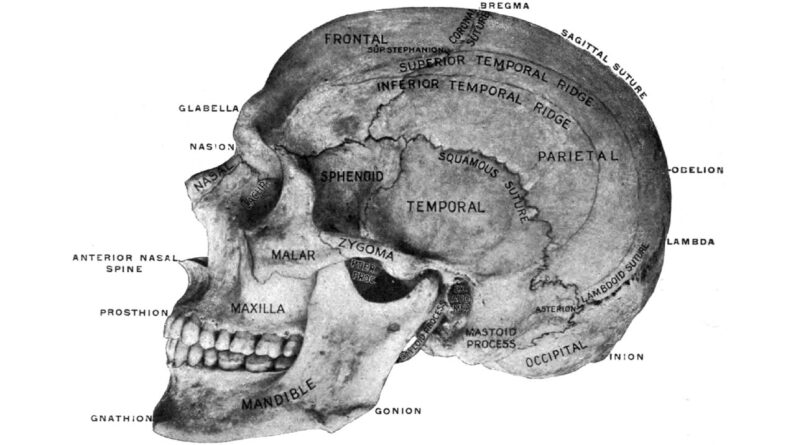

(Image credit: Frederick Henry Gerrish(1845-1920), Public domain, by means of Wikimedia Commons)

The current publication of the University of Edinburgh’s Evaluation of Race and History has actually accentuated its “skull room”: a collection of 1,500 human craniums obtained for research study in the 19th century.

Craniometry, the research study of skull measurements, was extensively taught in medical schools throughout

Britain, Europe, and the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Today, the damaging and racist structures of craniometry have actually been rejected. It’s long been shown that the shapes and size of the head have no bearing on psychological and behavioral qualities in either people or groups.

In the 19th and early 20th century, nevertheless, countless skulls were accumulated to make it possible for research study and direction in clinical bigotry. Edinburgh’s skull space is by no methods distinct.

Unlike phrenology, a popular theory which connected personality type to bumps on the head, craniometry delighted in prevalent clinical assistance in the 19th century since it focused on information collection and stats.

Related: What’s the distinction in between race and ethnic culture?

Craniometrists determined skulls and balanced the outcomes for various population groups. This information was utilized to categorize individuals into races based upon the shapes and size of the head. Craniometrical proof was utilized to describe why some individuals were allegedly more civilized and progressed than others.

Get the world’s most remarkable discoveries provided directly to your inbox.

The large build-up of information drawn from skulls interested Victorian researchers who thought in the neutrality of numbersIt similarly assisted to confirm racial bias by recommending that distinctions amongst individuals were natural and biologically identified.

Case historyThe research study of skulls was main to the advancement of 19th-century sociology. Before sociology was taught at British universities, markers of expected racial distinction were studied by anatomists knowledgeable in recognizing minute distinctions in skeletons. The research study of skulls got in the university curriculum through medical schools, and especially through anatomy departments.

When Alexander Macalister was designated as teacher of anatomy at Cambridge in 1884, a few of his very first lectures were on “The Race Types of the Human Skull.”

Macalister’s yearly report for 1892 in the Cambridge University Reporter explains how he had actually increased Cambridge’s cranial holdings from 55 to 1,402 specimens. In 1899, he reported the contribution of more than 1,000 ancient Egyptian craniums from the archaeologist Flinders Petrie. Much of Macalister’s skull collection stays housed in the university’s Duckworth Laboratorywhich was developed in 1945.

As the status of craniometrical research study increased, organizations needed to complete for cranial collections as they went on the marketplace. Analytical precision depended upon huge series of craniums being determined to produce representative “types”This developed an increased need for human remains.

An illustration of 2 males determining the capability of cranial cavity by methods of water. (Image credit: J.S. Billings and Washington Matthews, Public domain, through Wikimedia Commons )In 1880, the Royal College of Surgeons bought 1,539 skulls from the personal collection of Joseph Barnard DavisThis was contributed to their existing cache of 1,018 craniums to develop Britain’s biggest craniological collectionThis collection was mostly damaged in 1941 when the college structure was bombed throughout world war 2. The staying skulls are no longer held by the Royal College of Surgeons.

Oxford’s University Museum of Natural History consisted of rows of crania in their physiological screens in the 19th century, as did the University of Manchester’s medical school (the medical school is no longer on the exact same website). This financial investment in skulls made sure that racial scientists had sufficient product to study and utilize in their mentor.

Catalogues kept by universities in the 19th and early 20th centuries expose not just the size of their skull collections, however likewise the origin of specific specimens.

Historic injurySome medical schools, such as Edinburgh’srepurposed skulls obtained by phrenological societies previously in the century to improve their holdings. Others, consisting of Oxford’s, made usage of skulls discovered by archaeologists to carry out racial research study into the nation’s past. This research study tried to trace the motions of Celts, Normans, Saxons, and Scandinavians throughout the British Isles.

Since craniologists desired to record the complete degree of racial variation, skulls from abroad were specifically treasured. Medical graduates of British universities published to the nests sent out foreign bones to their old teachers.

In research study for my upcoming book on skull collections, I’ve discovered that Cambridge’s cranial register consists of a skull sent out from a previous trainee stationed in India. He had actually plucked it from a cremation website in Bombay in spite of the outrage of collected mourners. Brazen grave-robbing and colonial violence were main to the global network that provided British universities’ skull spaces.

The racist ideology that stimulated the collection of skulls 150 years back has actually been totally rejected. some anthropologists think these bones might still clarify human origins, relations and migrations.

Ethical aspects now similarly form institutional policies towards human remains. The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford took its notorious “shrunken heads” off screen in 2020.

Progressively, universities and museums have actually faced the historical oppressions and inter-generational injury perpetuated by their retention of human remainsBecause the 1970s, Indigenous groups from worldwide have actually introduced projects to repatriate their forefathers’ bones. Research study organizations have actually ended up being progressively responsive to these demands.

In London, the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons no longer shows the skeleton of Charles Byrnethe so-called “Irish Giant”Byrne had clearly rejected approval for his remains to be dissected and installed before he passed away in 1783.

The skulls in British universities are a testimony to a large theft of human remains from practically every area in the world. They have the possible to end up being effective signs of reconciliation if their prejudiced histories are acknowledged, and fixed through their return.

A representative for the Duckworth Laboratory, University of Cambridge, stated:

“We, like many institutions in the UK, are dealing with the legacies and past unethical practice in assembling the collections in our care. The Duckworth Collection and the Department of Archaeology are dedicated to fostering an open dialogue and building robust relationships with traditional communities and other stakeholders. This commitment is seen as an integral part of a continuous, reciprocal exchange of knowledge, perspectives, and cultural values. The aim is not only to address past inequities but also to enrich contemporary academic and cultural understanding through a respectful and equal partnership. In this vein, the Duckworth Collection is actively expanding its work with archival documentation and improving our records and database. In essence, the Duckworth Laboratory’s approach to repatriation and community engagement is marked by a commitment to openness, inclusivity, and a recognition of the need for an ongoing dialogue.”

This edited post is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Check out the initial post

Elise Smith is Associate Professor in the History of Medicine at the University of Warwick. She has actually composed on the history of military medication, human measurement, and physical sociology. She is presently finishing a book rising and fall of skull determining throughout the British Empire.

Learn more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.