VA Tech experiment was motivated by Death Valley’s mystical “sailing stones” at Racetrack Playa.

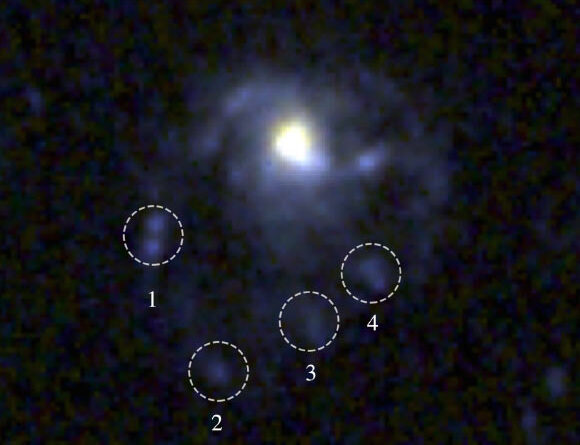

College student Jack Tapocik establishes ice on a crafted surface area in the VA Tech laboratory of Jonathan Boreyko.

Credit: Alex Parrish/Virginia Tech

Researchers have actually found out how to make frozen discs of ice self-propel throughout a patterned metal surface area, according to a brand-new paper released in the journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces. It’s the current development to come out of the Virginia Tech laboratory of mechanical engineer Jonathan Boreyko.

A couple of years earlier, Boreyko’s laboratory experimentally showed a three-phase Leidenfrost impact in water vapor, liquid water, and ice. The Leidenfrost result is what takes place when you rush a couple of drops of water onto a really hot, sizzling frying pan. The drops levitate, moving around the pan with wild desert. If the surface area is at least 400 ° Fahrenheit (well above the boiling point of water), cushions of water vapor, or steam, type beneath them, keeping them levitated. The impact likewise deals with other liquids, consisting of oils and alcohol, however the temperature level at which it manifests will be various.

Boreyko’s laboratory found that this impact can likewise be accomplished in ice merely by positioning a thin, flat disc of ice on a heated aluminum surface area. When the plate was heated up above 150 ° C(302 ° F), the ice did not levitate on a vapor the method liquid water does. Rather, there was a considerably greater limit of 550 ° Celsius (1,022 ° F) for levitation of the ice to happen. Unless that vital limit is reached, the meltwater listed below the ice simply keeps boiling in direct contact with the surface area. Cross that crucial point and you will get a three-phase Leidenfrost result.

The secret is a temperature level differential in the meltwater simply below the ice disc. The bottom of the meltwater is boiling, however the top of the meltwater stays with the ice. It takes a lot to preserve such a severe distinction in temperature level, and doing so takes in the majority of the heat from the aluminum surface area, which is why it’s more difficult to accomplish levitation of an ice disc. Ice can reduce the Leidenfrost impact even at really heats (approximately 550 ° C), which suggests that utilizing ice particles rather of liquid beads would be much better for numerous applications including spray quenching: quick cooling in nuclear reactor, for instance, firefighting, or fast heat satiating when forming metals.

This time around, Boreyko et al. have actually turned their attention to what the authors term “a more viscous analog” to a Leidenfrost cog, a kind of bead self-propulsion. “What’s different here is we’re no longer trying to levitate or even boil,” Boreyko informed Ars. “Now we’re asking a more straightforward question: Is there a way to make ice move across the surface directionally as it is melting? Regular melting at room temperature. We’re not boiling, we’re not levitating, we’re not Leidenfrosting. We just want to know, can we make ice shoot across the surface if we design a surface in the right way?”

Strange moving stones

The scientists were motivated by Death Valley’s well-known “sailing stones” on Racetrack Playa. Watermelon-sized stones are scattered throughout the dry lake bed, and they leave tracks in the broken earth as they gradually move a number of hundred meters each season. Researchers didn’t determine what was occurring till 2014. Co-author Ralph Lorenz (Johns Hopkins University) confessed he believed theirs would be “the most boring experiment ever” when they initially set it up in 2011, 2 years later on, the stones did certainly start to move while the playa was covered with a pond of water a couple of inches deep.

Lorenz and his co-authors were lastly able to recognize the system. The ground is too tough to soak up rains, which water freezes when the temperature level drops. When temperature levels increase above freezing once again, the ice begins to melt, developing ice rafts drifting on the meltwater. And when the winds are adequately strong, they trigger the ice rafts to wander along the surface area.

A cruising stone at Death Valley’s Racetrack Playa.

Credit: Tahoenathan/CC BY-SA 3.0

“Nature had to have wind blowing to kind of push the boulder and the ice along the meltwater that was beneath the ice,” stated Boreyko. “We thought, what if we could have a similar idea of melting ice moving directionally but use an engineered structure to make it happen spontaneously so we don’t have to have energy or wind or anything active to make it work?”

The group made their ice discs by putting pure water into thermally insulated polycarbonate Petrie meals. This led to bottom-up freezing, which decreases air bubbles in the ice. They then crushed uneven grooves into uncoated aluminum plates in a herringbone pattern– basically developing arrowhead-shaped channels– and after that bonded them to warmers warmed to the preferred temperature level. Each ice disc was put on the plate with rubber tongs, and the experiments were recorded from numerous angles to totally record the disc habits.

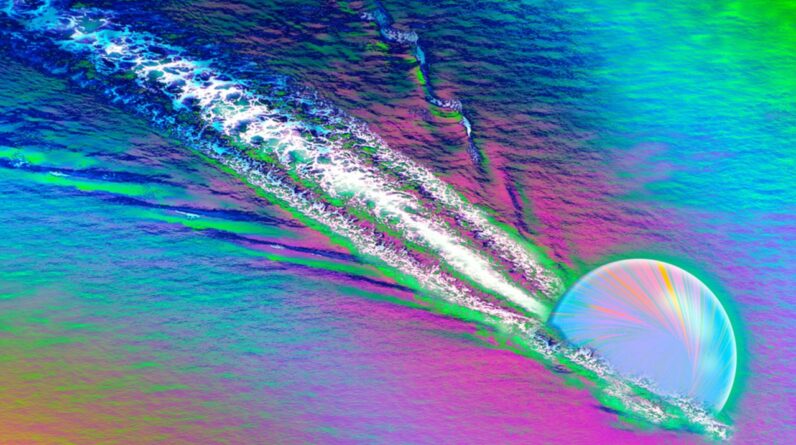

The herringbone pattern is the secret. “The directionality is what really pushes the water,” Jack Tapocik, a college student in Boreyko’s laboratory, informed Ars. “The herringbone doesn’t allow for water to flow backward, the water has to go forward, and that basically pushes the water and the ice together forward. We don’t have a treated surface, so the water just sits on top and the ice all moves as one unit.”

Boreyko draws an example to tubing on a river, other than it’s the directional channels instead of gravity triggering the circulation. “You can see [in the video below] how it just follows the meltwater,” he stated. “This is your classic entrainment mechanism where if the water flows that way and you’re floating on the water, you’re going to go the same way, too. It’s basically the same idea as what makes a Leidenfrost droplet also move one way: It has a vapor flow underneath. The only difference is that was a liquid drifting on a vapor flow, whereas now we have a solid drifting on a liquid flow. The densities and viscosities are different, but the idea is the same: You have a more dense phase that is drifting on the top of a lighter phase that is flowing directionally.”

Jonathan Boreyko/Virginia Tech

Next, the group duplicated the experiment, this time covering the aluminum herringbone surface area with water-repellant spray, wanting to accelerate the disc propulsion. Rather, they discovered that the disc wound up adhering to the dealt with surface area for a while before all of a sudden slingshotting throughout the metal plate.

“It’s a totally different concept with totally different physics behind it, and it’s so much cooler,” stated Tapocik. “As the ice is melting on these coated surfaces, the water just doesn’t want to sit within the channels. It wants to sit on top because of the [hydrophobic] coating we have on there. The ice is directly sticking now to the surface, unlike before when it was floating. You get this elongated puddle in front. The easiest place [for the ice] to be is in the center of this giant, long puddle. So it re-centers, and that’s what moves it forward like a slingshot.”

Basically, the water keeps broadening asymmetrically, which distinction fit triggers an inequality in surface area stress since the quantity of force that surface area stress puts in on a body depends upon curvature. The flatter puddle shape in front has less curvature than the smaller sized shape in back. As the video listed below programs, when the inequality in surface area stress ends up being adequately strong, “It just rips the ice off the surface and flings it along,” stated Boreyko. “In the future, we could try putting little things like magnets on top of the ice. We could probably put a boulder on it if we wanted to. The Death Valley effect would work with or without a boulder because it’s the floating ice raft that moves with the wind.”

Jonathan Boreyko/Virginia Tech

One prospective application is energy harvesting. One might pattern the metal surface area in a circle rather than a straight line so the melting ice disk would constantly turn. Put magnets on the disk, and they would likewise turn and create power. One may even connect a turbine or equipment to the turning disc.

The result may likewise offer a more energy-efficient methods of defrosting, a longstanding research study interest for Boreyko. “If you had a herringbone surface with a frosting problem, you could melt the frost, even partially, and use these directional flows to slingshot the ice off the surface,” he stated. “That’s both faster and uses less energy than having to entirely melt the ice into pure water. We’re looking at potentially over a tenfold reduction in heating requirements if you only have to partially melt the ice.”

That stated, “Most practical applications don’t start from knowing the application beforehand,” stated Boreyko. “It starts from ‘Oh, that’s a really cool phenomenon. What’s going on here?’ It’s only downstream from that it turns out you can use this for better defrosting of heat exchangers for heat pumps. I just think it’s fun to say that we can make a little melting disk of ice very suddenly slingshot across the table. It’s a neat way to grab your attention and think more about melting and ice and how all this stuff works.”

DOI: ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, 2025. 10.1021/ acsami.5 c08993 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior author at Ars Technica with a specific concentrate on where science fulfills culture, covering whatever from physics and associated interdisciplinary subjects to her preferred movies and television series. Jennifer resides in Baltimore with her partner, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their 2 felines, Ariel and Caliban.

22 Comments

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.