more than a marital relationship of benefit

Author Laurie Gwen Shapiro talks with Ars about her newest book, The Aviator and the Showman

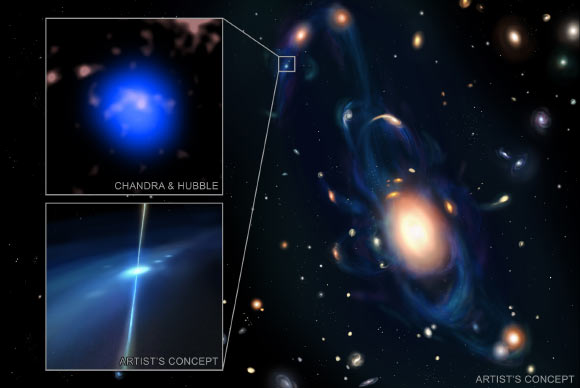

Amelia Earhart.

Credit: Public domain

Well known pilot Amelia Earhart has actually recorded our creativities for almost a century, especially her disappearance in 1937 throughout an effort to end up being the very first female pilot to circumnavigate the world. Earhart was a complex female, extremely proficient as a pilot yet with a propensity towards negligence. And her marital relationship to a flamboyant publisher with a style for marketing might have motivated that recklessness and added to her unforeseen death, according to a remarkable brand-new book, The Aviator and the Showman: Amelia Earhart, George Putnam, and the Marriage that Made an American Icon

Author Laurie Gwen Shapiro is a long time Earhart fan. A documentary filmmaker and reporter, she initially checked out Earhart in a brief bio dispersed by Scholastic Books. “I got a little obsessed with her when I was younger,” Shapiro informed Ars. The fascination faded as she aged and introduced her own profession. She found her enthusiasm for Earhart while composing her 2018 book, The Stowawayabout a boy who stashed on Admiral Richard Byrd’s very first trip to Antarctica. The marketing mastermind behind the kid’s journey and his subsequent (ghost-written) narrative was publisher George Palmer Putnam, Earhart’s ultimate spouse.

The truth that Earhart began as Putnam’s girlfriend opposed Shapiro’s early squeaky-clean picture of Earhart and drove her to dig much deeper into the life of this amazing lady. “I was less interested in how she died than how she lived,” stated Shapiro. “Was she a good pilot? Was she a good, kind person? Was this a real marriage? The mystery of Amelia Earhart is not how she died, but how she lived.”

There have actually been various Earhart bios, however Shapiro accessed some fairly brand-new source product, most significantly an excellent 200 hours of tapes that had actually appeared by means of the Smithsonian’s Amelia Earhart Project, consisting of interviews with Earhart’s sibling, Muriel. “I took an extra six months on my book just so that I could listen to all of them,” stated Shapiro. She likewise searched archival product at the University of New Hampshire worrying Putnam’s close partner, Hilton Railey; at Purdue University; and at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute, in addition to many in-person interviews– consisting of numerous with authors of previous Earhart bios.

Shapiro’s breezy account of Earhart’s early life consists of a couple of brand-new information, especially about the pilot’s relationship with an early benefactor (Shapiro calls him Earhart’s “sugar daddy”in California: a 63-year-old signboard tycoon called Thomas Humphrey Bennett Varney. Varney wished to wed her, however she wound up accepting the proposition of a young chemical engineer from Boston, Samuel Chapman. “Amelia could have had a very different life,” stated Shapiro. “She could have gone to Marblehead, Massachusetts, where [Chapman] had a house, and become part of the yacht set and she still would have had an interesting life. But I don’t think that was the life Amelia Earhart wanted, even if that meant she had a shorter life.”

Shapiro does not overlook Putnam’s story, explaining him as the “PT Barnum of publishing.” The household publishing business, G.P. Putnam and Sons, was established in 1838 by his grandpa, and by the late 1920s, the enthusiastic young George was amongst numerous possible followers jockeying for position to change his uncle, George Haven Putnam. He had his own aspirations, figured out to bring what he considered as a stodgy business totally into the 20th century.

Putnam released Charles Lindbergh’s hit narrative, Wein 1927 and followed that early success with a series of rather lurid experience memoirs narrating the exploits of “boy explorers.” The young boys didn’t constantly endure their experiences, with one diing from a snake bite and another drowning in a Bolivian flood. The books were business successes, so Putnam kept cranking them out.

After Lindbergh’s historical crossing, Putnam aspired to take advantage of the general public’s thirst for air travel stories. It would not be particularly relevant to have another male make the very same flight. A female? Putnam liked that concept, and a rich benefactor, steel heiress Amy Phipps Guest, supplied financial backing for the accomplishment– truly more of a promotion stunt, because Putnam’s strategy, as constantly, was to release a scintillating narrative of the journey. Throughout allure Age, papers consistently spent for unique rights to these sort of stories in exchange for radiant protection, per Shapiro. In this case, The New York Times did not at first wish to sponsor a lady for a trans-Atlantic flight, however Putnam’s connections won them over.

Love at very first sight

Earhart, then a social employee living in Boston, spoke with to be part of the three-person team making that historical 1928 trans-Atlantic flight, and Putnam rapidly identified her capacity to be his brand-new experience heroine. Railey later on remembered that, a minimum of for Putnam– whose marital relationship to Crayola heiress Dorothy Binney was going to pieces– it was love at very first sight.

At the time, Earhart was still engaged to Chapman, and George was still wed to Binney, however nevertheless, he “relentlessly pursued” Earhart. Earhart ended her engagement to Chapman in November 1928. “There’s a tape in the Smithsonian archives that talks about his wife coming in and catching them in sexual relations,” stated Shapiro. “But [Binney] was having an affair, too, with a young man named George Weymouth [her son’s tutor]. This is the Jazz Age, anything goes. Amelia wanted to be able to achieve her dreams. Who are we to say a woman can’t marry a man who can give her a path to being wealthy?”

The effective 1928 flight made Earhart the name “Lady Lindy.” Putnam showered his girlfriend with fur coats, stylish vehicles, and other elegant features– although as her supervisor, he still kept 10 percent of her revenues. That life of high-end broke down in October 1929 with the beginning of the Great Depression, and Putnam discovered himself rushing economically after being pressed out of the household publishing business.

Earhart and Putnam in 1931.

Public domain

After his rather untidy divorce from Binney, Putnam wed Earhart in 1931. Earhart held distinctly non-traditional views on marital relationship for that age: They held different savings account, and she kept her first name, seeing the marital relationship as a “partnership” with “dual control,” and firmly insisting in a letter to Putnam on their big day that she would not need fidelity. “I may have to keep some place where I can go to be myself, now and then, for I cannot guarantee to endure at all times the confinement of even an attractive cage,” she composed.

Given that cash was tight, Putnam motivated Earhart to go on the lecture circuit. Earhart would perform a stunt flight, compose a book about it, and after that go on a lecture trip. “This is an actual marriage,” stated Shapiro. “It might have started out more romantically, but at a certain point, they needed each other in a partnership to survive. We don’t have fairy tale connections. Sometimes we have a hot romance that turns into a partnership and then cycles back into intense closeness and mental separation. I think that was the case with Amelia and George.”

Came Earhart’s eventful last battle. The night before her scheduled departure, an anxious Earhart wished to wait, however Putnam currently had strategies in the works for yet another flight, funded through sponsorship offers. And he wished to get the resulting book about the existing pending flight out in time for Christmas. He encouraged her to take off as prepared. Her navigator, Fred Noonan, was proficient at his task, however he was a problem drinker, so he came inexpensive. That choice was among numerous that would show expensive.

Shapiro explains this flight as being “plagued with mechanical issues from the start, underprepared and over-hyped, a feat of marketing more than a feat of engineering.” And she does not discharge Earhart from blame. “She refused to learn Morse code,” stated Shapiro. “She refused to hear that trying to land on Howland Island was almost a suicide mission. It’s almost certain that she ran out of gas. Amelia was a very good person, a decent flyer, and beyond brave. She brought up women and championed feminism when other technically more gifted women pilots were going for solo records and had no time for their peers. She aided the aviation industry during the Great Depression as a likable ambassador of the air.”

Shapiro thinks that Earhart’s marital relationship to Putnam magnified her incautious impulses, with awful repercussions on her last flight. “Is it George’s fault, or is it Amelia’s fault? I don’t think that’s fair to say,” she stated. In numerous methods, the 2 matched each other. Like Putnam, Earhart had fantastic aspiration, and her marital relationship to Putnam allowed her to accomplish her objectives.

The other hand is that they likewise drew out each other’s less favorable qualities. “They were both aware of the risks involved in what they were doing,” Shapiro stated. “But I also tried to show that there was a pattern of both of them taking extraordinary risks without really worrying about critical details. Yes, there is tremendous bravery in [undertaking] all these flights, but bravery is not always enough when charisma trumps caution—and when the showman insists the show must go on.”

Jennifer is a senior author at Ars Technica with a specific concentrate on where science satisfies culture, covering whatever from physics and associated interdisciplinary subjects to her preferred movies and television series. Jennifer resides in Baltimore with her partner, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their 2 felines, Ariel and Caliban.

34 Comments

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.