“That’s exactly the kind of thing that NASA should be concentrating its resources on.”

Artist’s illustration of the DRACO nuclear rocket engine in area.

Credit: Lockheed Martin

New information of the Trump administration’s prepare for NASA, launched Friday, exposed the White House’s desire to end the advancement of a speculative nuclear thermal rocket engine that might have revealed a brand-new method of checking out the Solar System.

Trump’s NASA budget plan demand is swarming with costs cuts. In general, the White House proposes decreasing NASA’s spending plan by about 24 percent, from $24.8 billion this year to $18.8 billion in 2026. In previous stories, Ars has actually covered a lot of the programs affected by the proposed cuts, which would cancel the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft and end many robotic science objectives, consisting of the Mars Sample Return, probes to Venus, and future area telescopes.

Rather, the remaining financing for NASA’s human expedition program would approach supporting industrial jobs to arrive at the Moon and Mars.

NASA’s efforts to leader next-generation area innovations are likewise struck hard in the White House’s spending plan proposition. If the Trump administration gets its method, NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate, or STMD, will see its spending plan cut almost in half, from $1.1 billion to $568 million.

Trump’s spending plan demand isn’t last. Both Republican-controlled homes of Congress will compose their own variations of the NASA spending plan, which need to be fixed up before going to the White House for President Trump’s signature.

“The budget reduces Space Technology by approximately half, including eliminating failing space propulsion projects,” the White House composed in a preliminary introduction of the NASA budget plan demand launched May 2. “The reductions also scale back or eliminate technology projects that are not needed by NASA or are better suited to private sector research and development.”

Breathing fire

Recently, the White House and NASA put a finer point on these “failing space propulsion projects.”

“This budget provides no funding for Nuclear Thermal Propulsion and Nuclear Electric Propulsion projects,” authorities composed in a technical supplement launched Friday detailing Trump’s NASA spending plan proposition. “These efforts are costly investments, would take many years to develop, and have not been identified as the propulsion mode for deep space missions. The nuclear propulsion projects are terminated to achieve cost savings and because there are other nearer-term propulsion alternatives for Mars transit.”

Primary amongst these cuts, the White House proposes to end NASA’s involvement in the Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Operations (DRACO) job. NASA stated this proposition “reflects the decision by our partner to cancel” the DRACO objective, which would have shown a nuclear thermal rocket engine in area for the very first time.

NASA’s partner on the DRACO objective was the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, the Pentagon’s research study and advancement arm. A DARPA representative verified the firm was liquidating the task.

“DARPA has completed the agency’s involvement in the Demonstration Rocket for Agile Cislunar Orbit (DRACO) program and is transitioning its knowledge to our DRACO mission partner, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and to other potential DOD programs,” the representative stated in an action to composed concerns.

A nuclear rocket engine, which was to be part of NASA’s aborted NERVA program, is checked at Jackass Flats, Nevada, in 1967.

Credit: Corbis through Getty Images)

Less than 2 years back, NASA and DARPA revealed strategies to move on with the approximately$500 million DRACO job, targeting a launch into Earth orbit aboard a standard chemical rocket in 2027. “With the help of this new technology, astronauts could journey to and from deep space faster than ever, a major capability to prepare for crewed missions to Mars,” previous NASA administrator Bill Nelson stated at the time.

The DRACO objective would have included a number of aspects, consisting of an atomic power plant to quickly warm up super-cold liquid hydrogen fuel saved in an insulated tank onboard the spacecraft. Temperature levels inside the engine would reach almost 5,000 ° Fahrenheit, boiling the hydrogen and driving the resulting gas through a nozzle, creating thrust. From the outdoors, the spacecraft’s style looks a lot like the upper phase of a standard rocket. In theory, a nuclear thermal rocket engine like DRACO’s would use two times the effectiveness of the highest-performing traditional rocket engines. That equates to substantially less fuel that an objective to Mars would need to bring throughout the Solar System.

Basically, a nuclear thermal rocket engine integrates the high-thrust ability of a chemical engine with a few of the fuel effectiveness advantages of low-thrust solar-electric engines. With DRACO, engineers looked for tough information to validate their understanding of nuclear propulsion and wished to ensure the nuclear engine’s tough style really worked. DRACO would have utilized high-assay low-enriched uranium to power its atomic power plant.

Nuclear electrical propulsion utilizes an onboard atomic power plant to power plasma thrusters that develop thrust by speeding up an ionized gas, like xenon, through an electromagnetic field. Nuclear electrical propulsion would offer another leap in engine performance beyond the abilities of a system like DRACO and might eventually use the most appealing choice for withstanding deep area transport.

NASA led the advancement of DRACO’s nuclear rocket engine, while DARPA was accountable for the total spacecraft style, operations, and the tough issue of protecting regulative approval to release an atomic power plant into orbit. The reactor on DRACO would have released in “cold” mode before triggering in area, lowering the danger to individuals on the ground in case of a launch mishap. The Space Force consented to spend for DRACO’s launch on a United Launch Alliance Vulcan rocket.

DARPA and NASA chose Lockheed Martin as the lead specialist for the DRACO spacecraft in 2023. BWX Technologies, a leader in the United States nuclear market, won the agreement to establish the objective’s reactor.

“We received the notice from DARPA that it ended the DRACO program,” a Lockheed Martin representative stated. “While we’re disappointed with the decision, it doesn’t change our vision of how nuclear power influences how we will explore and operate in the vastness of space.”

Bogged down in the laboratory

More than 60 years have actually passed because a US-built atomic power plant introduced into orbit. Air travel Week reported in January that a person issue dealing with DRACO engineers included concerns about how to securely check the nuclear thermal engine on the ground while sticking to nuclear security procedures.

“We’re bringing two things together—space mission assurance and nuclear safety—and there’s a fair amount of complexity,” stated Matthew Sambora, a DRACO program supervisor at DARPA, in an interview with Aviation Week. At the time, DARPA and NASA had actually currently quit on a 2027 launch to focus on establishing a model engine utilizing helium as a propellant before carrying on to a functional engine with more energetic liquid hydrogen fuel, Aviation Week reported.

Greg Meholic, an engineer at the Aerospace Corporation, highlighted the deficiency in ground screening ability in a discussion in 2015. Nuclear thermal propulsion screening “requires that engine exhaust be scrubbed of radiologics before being released,” he composed. This requirement “could result in substantially large, prohibitively expensive facilities that take years to build and qualify.”

These security procedures weren’t as strict when NASA and the Air Force initially pursued nuclear propulsion in the 1960s. Now, the very first severe 21st-century effort to fly a nuclear rocket engine in area is grinding to a stop.

“Given that our near-term human exploration and science needs do not require nuclear propulsion, current demonstration projects will end,” composed Janet Petro, NASA’s acting administrator, in a letter accompanying the Trump administration’s spending plan release recently.

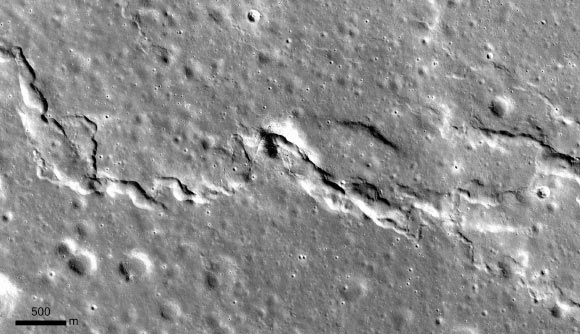

This figure highlights the significant components of a normal nuclear thermal rocket engine.

Credit: NASA/Glenn Research Center

NASA’s 2024 budget plan designated$117 million for nuclear propulsion work, a boost from$91 million the previous year. Congress included more financing for NASA’s nuclear propulsion programs over the Biden administration’s proposed budget plan recently, signifying assistance on Capitol Hill that might conserve a minimum of some nuclear propulsion efforts next year.

It’s real that nuclear propulsion isn’t needed for any NASA objectives presently on the books. Today’s rockets are proficient at tossing freight and individuals off world Earth, once a spacecraft gets here in orbit, there are numerous methods to move it towards more far-off locations.

NASA’s existing architecture for sending out astronauts to the Moon utilizes the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft, both of which are proposed for cancellation and look a lot like the automobiles NASA utilized to fly astronauts to the Moon more than 50 years back. SpaceX’s multiple-use Starship, developed with an eye towards settling Mars, utilizes traditional chemical propulsion, with methane and liquid oxygen propellants that SpaceX one day wishes to produce on the surface area of the Red Planet.

NASA, SpaceX, and other business do not require nuclear propulsion to beat China back to the Moon or put the very first human footprints on Mars. There’s a broad agreement that in the long run, nuclear rockets provide a much better method of moving around the Solar System.

The armed force’s intention for moneying nuclear thermal propulsion was its capacity for ending up being a more effective methods of steering around the Earth. A number of the armed force’s crucial spacecraft are restricted by fuel, and the Space Force is examining orbital refueling and unique propulsion approaches to extend the life-span of satellites.

NASA’s nuclear power program is not completed. The Trump administration’s spending plan proposition requires continued financing for the firm’s fission surface area power program, with the objective of fielding an atomic power plant that might power a base upon the surface area of the Moon or Mars. Lockheed and BWXT, the professionals associated with the DRACO objective, belong to the fission surface area power program.

There is some financing in the White House’s budget plan ask for tech demonstrations utilizing other approaches of in-space propulsion. NASA would continue moneying experiments in long-lasting storage and transfer of cryogenic propellants like liquid methane, liquid hydrogen, and liquid oxygen. These joint jobs in between NASA and market might lead the way for orbital refueling and orbiting propellant depots, lining up with the instructions of business like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and United Launch Alliance.

Lots of researchers and engineers think nuclear propulsion provides the only reasonable course for a sustainable project shuttling individuals in between the Earth and Mars. A report commissioned by NASA and the National Academies concluded in 2021 that an aggressive tech-development program might advance nuclear thermal propulsion enough for a human exploration to Mars in 2039. The potential customers for nuclear electrical propulsion were murkier.

This would have needed NASA to considerably increase its spending plan for nuclear propulsion right away, most likely by an order of magnitude beyond the firm’s standard financing level, or to a quantity surpassing $1 billion each year, stated Bobby Braun, co-chair of the National Academies report, in a 2021 interview with Ars. That didn’t take place.

Going nuclear

The interplanetary transport architectures pictured by NASA and SpaceX will, a minimum of at first, mostly utilize chemical propulsion for the cruise in between Earth and Mars.

Kurt Polzin, primary engineer of NASA’s area nuclear propulsion tasks, stated considerable technical difficulties stand in the method of any propulsion system chosen to power heavy freight and human beings to Mars.

“Anybody who says that they’ve solved the problem, you don’t know that because you don’t have enough data,” Polzin stated recently at the Humans to the Moon and Mars Summit in Washington.

“We know that to do a Mars mission with a Starship, you need lots of refuelings at Earth, you need lots of refuelings at Mars, which you have to send in advance,” Polzin stated. “You either need to send that propellant in advance or send a bunch of material and hardware to the surface to be set up and robotically make your propellant in situ while you’re there.”

Elon Musk’s SpaceX is banking on chemical propulsion for round-trip flights to Mars with its Starship rocket. This will need assembly of propellant-generation plants on the Martian surface area.

Credit: SpaceX

Recently, SpaceX creator Elon Musk laid out how the business prepares to land its very first Starships on Mars. His roadmap consists of more than 100 freight flights to provide devices to produce methane and liquid oxygen propellants on the surface area of Mars. This is essential for any Starship to introduce off the Red Planet and go back to Earth.

“You can start to see that this starts to become a Rube Goldberg way to do Mars,” Polzin stated. “Will I say it can’t work? No, but will I say that it’s really, really difficult and challenging. Are there a lot of miracles to make it work? Absolutely. So the notion that SpaceX has solved Mars or is going to do Mars with Starship, I would challenge that on its face. I don’t think the analysis and the data bear that out.”

Engineers understand how methane-fueled rocket engines carry out in area. Researchers have actually developed liquid oxygen and liquid methane given that the late 1800s. Scaling up a propellant plant on Mars to produce countless lots of cryogenic liquids is another matter. In the long run, this may be an appropriate option for Musk’s vision of producing a city on Mars, however it features tremendous start-up expenses and threats. Still, nuclear propulsion is a totally untried innovation.

“The thing with nuclear is there are challenges to making it work, too,” Polzin stated. “However, all of my challenges get solved here at Earth and in low-Earth orbit before I leave. Nuclear is nice. It has a higher specific impulse, especially when we’re talking about nuclear thermal propulsion. It has high thrust, which means it will get our astronauts there and back quickly, but I can carry all the fuel I need to get back with me, so I don’t need to do any complicated refueling at Mars. I can return without having to make propellant or send any pre-positioned propellant to get back.”

The yank of war over nuclear propulsion is absolutely nothing brand-new. The Air Force began a program to establish reactors for nuclear thermal rockets at the height of the Cold War. NASA took control of the Air Force’s function a couple of years later on, and the task continued into the next stage, called the Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application (NERVA). President Richard Nixon eventually canceled the NERVA job in 1973 after the federal government had actually invested $1.4 billion on it, comparable to about $10 billion in today’s dollars. Regardless of almost twenty years of work, NERVA never ever flew in area.

Doing the tough things

The Pentagon and NASA studied numerous more nuclear thermal and nuclear electrical propulsion efforts before DRACO. Today, there’s a nascent industrial service case for compact atomic power plants beyond simply the federal government. There’s little industrial interest in installing a full-blown nuclear propulsion presentation entirely with personal financing.

Fred Kennedy, co-founder and CEO of an area nuclear power business called Dark Fission, stated a lot of equity capital financiers do not have the hunger to wait on monetary returns in nuclear propulsion that they might see in 15 or 20 years.

“It’s a truism: Space is hard,” stated Kennedy, a previous DARPA program supervisor. “Nuclear turns out to be hard for reasons we can all understand. So space-nuclear is hard-squared, folks. As a result, you give this to your average associate at a VC firm and they get scared quick. They see the moles all over your face, and they run away screaming.”

Industrial launch expenses are coming down. With continual federal government financial investment and structured guidelines, “this is the best chance we’ve had in a long time” to get a nuclear propulsion system into area, Kennedy stated.

Specialists prepare a nozzle for a model nuclear thermal rocket engine in 1964.

Credit: NASA

“I think, right now, we’re in this transitional period where companies like mine are going have to rely on some government largesse, as well as hopefully both commercial partnerships and honest private investment,” Kennedy stated. “Three years ago, I would have told you I thought I could have done the whole thing with private investment, but three years have turned my hair white.”

Those who share Kennedy’s view believed they were getting an ally in the Trump administration. Jared Isaacman, the billionaire business astronaut Trump chose to end up being the next NASA administrator, assured to focus on nuclear propulsion in his period as head of the country’s area company.

Throughout his Senate verification hearing in April, Isaacman stated NASA needs to turn over management of heavy-lift rockets, human-rated spacecraft, and other tasks to business market. This modification, he stated, would enable NASA to concentrate on the “near-impossible challenges that no company, organization, or agency anywhere in the world would be able to undertake.”

The example Isaacman gave up his verification hearing was nuclear propulsion. “That’s something that no company would ever embark upon,” he informed legislators. “There is no obvious economic return. There are regulatory challenges. That’s exactly the kind of thing that NASA should be concentrating its resources on.”

The White House all of a sudden revealed on Saturday that it was withdrawing Isaacman’s election days before the Senate was anticipated to verify him for the NASA post. While there’s no sign that Trump’s withdrawal of Isaacman had anything to do with any particular part of the White House’s financing strategy, his elimination leaves NASA without a supporter for nuclear propulsion and a variety of other tasks falling under the White House’s spending plan ax.

Stephen Clark is an area press reporter at Ars Technica, covering personal area business and the world’s area firms. Stephen blogs about the nexus of innovation, science, policy, and organization on and off the world.

193 Comments

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.