Avoid to content

“Hey, this is a very precarious situation we’re in.”

NASA astronaut Butch Wilmore gets a warm welcome at Johnson Space Center’s Ellington Field in Houston from NASA astronauts Reid Wiseman and Woody Hoburg after finishing a long-duration science objective aboard the International Space Station.

Credit: NASA/Robert Markowitz

NASA astronaut Butch Wilmore gets a warm welcome at Johnson Space Center’s Ellington Field in Houston from NASA astronauts Reid Wiseman and Woody Hoburg after finishing a long-duration science objective aboard the International Space Station.

Credit: NASA/Robert Markowitz

As it flew up towards the International Space Station last summertime, the Starliner spacecraft lost 4 thrusters. A NASA astronaut, Butch Wilmore, needed to take manual control of the lorry. As Starliner’s thrusters stopped working, Wilmore lost the capability to move the spacecraft in the instructions he desired to go.

He and his fellow astronaut, Suni Williams, understood where they wished to go. Starliner had actually flown to within a stone’s toss of the spaceport station, a safe harbor, if just they might reach it. Currently, the failure of so lots of thrusters breached the objective’s flight guidelines. In such a circumstances, they were expected to reverse and return to Earth. Approaching the station was considered too dangerous for Wilmore and Williams, aboard Starliner, in addition to for the astronauts on the $100 billion spaceport station.

What if it was not safe to come home, either?

“I don’t know that we can come back to Earth at that point,” Wilmore stated in an interview. “I don’t know if we can. And matter of fact, I’m thinking we probably can’t.”

Starliner astronauts consult with the media

On Monday, for the very first time given that they went back to Earth on a Crew Dragon lorry 2 weeks back, Wilmore and Williams took part in a press conference at Johnson Space Center in Houston. Later, they invested hours performing short, 10-minute interviews with press reporters from worldwide, explaining their objective. I spoke to both of them.

A lot of the concerns worried the politically untidy end of the objective, in which the Trump White House declared it had actually saved the astronauts after they were stranded by the Biden administration. This was not real, however it is likewise not a concern that active astronauts are going to address. They have excessive regard for the company and the White House that designates its management. They are trained not to speak up of school. As Wilmore stated consistently on Monday, “I can’t speak to any of that. Nor would I.”

When Ars satisfied with Wilmore at the end of the day– it was his last interview, arranged for 4:55 to 5:05 pm in a little studio at Johnson Space Center– politics was not on the menu. Rather, I needed to know the genuine story, the heretofore unknown story of what it was truly like to fly Starliner. The issues with the spacecraft’s propulsion system sped up all the other occasions– the choice to fly Starliner home without team, the reshuffling of the Crew-9 objective, and their current return in March after 9 months in area.

I have actually understood Wilmore a bit for more than a years. I was fortunate to see his launch on a Soyuz rocket from Kazakhstan in 2014, along with his household. We both will end up being empty nesters, with children who are senior citizens in high school, quickly to go off to college. Maybe due to the fact that of this, Wilmore felt comfy sharing his experiences and stress and anxieties from the flight. We blew through the 10-minute interview slot and wound up talking for almost half an hour.

It’s a hell of a story.

Release and a cold night

Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft dealt with several hold-ups before the car’s very first crewed objective, bring NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams released on June 5, 2024. These consisted of a defective valve on the Atlas V rocket’s upper phase, and after that a helium leakage inside Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft.

The valve concern, in early May, stood the objective down enough time that Wilmore asked to fly back to Houston for extra time in a flight simulator to keep his abilities fresh. With great weather condition, the Starliner Crew Flight Test took off from Cape Canaveral, Florida. It marked the very first human launch on the Atlas V rocket, which had a brand-new Centaur upper phase with 2 engines.

Suni Williams ‘opening night on Starliner was rather cold.

Credit: NASA/Helen Arase Vargas

Suni Williams’opening night on Starliner was rather cold.

Credit: NASA/Helen Arase Vargas

Sunita “Suni” Williams: “Oh man, the launch was awesome. Both of us looked at each other like, ‘Wow, this is going just perfectly.’ So the ride to space and the orbit insertion burn, all perfect.”

Barry “Butch” Wilmore: “In simulations, there’s always a deviation. Little deviations in your trajectory. And during the launch on Shuttle STS-129 many years ago, and Soyuz, there’s the similar type of deviations that you see in this trajectory. I mean, it’s always correcting back. But this ULA Atlas was dead on the center. I mean, it was exactly in the crosshairs, all the way. It was much different than what I’d expected or experienced in the past. It was exhilarating. It was fantastic. Yeah, it really was. The dual-engine Centaur did have a surge. I’m not sure ULA knew about it, but it was obvious to us. We were the first to ride it. Initially we asked, ‘Should that be doing that? This surging?’ But after a while, it was kind of soothing. And again, we were flying right down the middle.”

After Starliner separated from the Atlas V rocket, Williams and Wilmore carried out numerous maneuvering tests and put the lorry through its rates. Starliner carried out remarkably well throughout these preliminary tests on the first day.

Wilmore: “The precision, the ability to control to the exact point that I wanted, was great. There was very little, almost imperceptible cross-control. I’ve never given a handling qualities rating of “one,” which was part of a measurement system. To take a qualitative test and make a quantitative assessment. I’ve never given a one, ever, in any test I’ve ever done, because nothing’s ever deserved a one. Boy, I was tempted in some of the tests we did. I didn’t give a one, but it was pretty amazing.”

Following these tests, the team tried to sleep for a number of hours ahead of their necessary technique and docking with the International Space Station on the flight’s 2nd day. More so even than launch or landing, the most tough part of this objective, which would worry Starliner’s dealing with abilities along with its navigation system, would come as it approached the orbiting lab.

Williams: “The night that we spent there in the spacecraft, it was a little chilly. We had traded off some of our clothes to bring up some equipment up to the space station. So I had this small T-shirt thing, long-sleeve T-shirt, and I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m cold.’ Butch is like, ‘I’m cold, too.’ So, we ended up actually putting our boots on, and then I put my spacesuit on. And then he’s like, maybe I want mine, too. So we both actually got in our spacesuits. It might just be because there were two people in there.”

Starliner was developed to fly 4 individuals to the International Space Station for six-month remain in orbit. For this preliminary test flight, there were simply 2 individuals, which suggested less body heat. Wilmore approximated that it had to do with 50 ° Fahrenheit in the cabin.

Wilmore: “It was definitely low 50s, if not cooler. When you’re hustling and bustling, and doing things, all the tests we were doing after launch, we didn’t notice it until we slowed down. We purposely didn’t take sleeping bags. I was just going to bungee myself to the bulkhead. I had a sweatshirt and some sweatpants, and I thought, I’m going to be fine. No, it was frigid. And I even got inside my space suit, put the boots on and everything, gloves, the whole thing. And it was still cold.”

Time to dock with the spaceport station

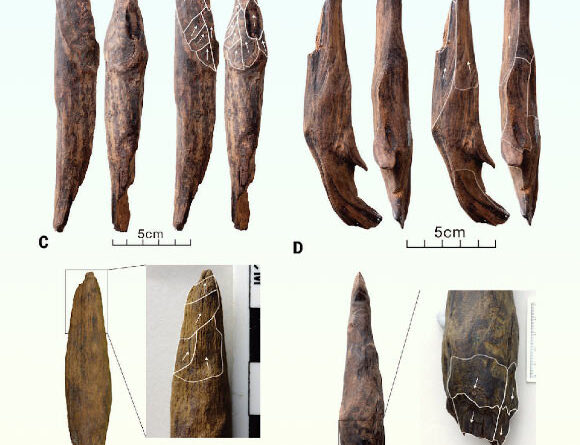

After a couple of hours of fitful sleep, Wilmore chose to get up and begin working to get his blood pumping. He examined the flight strategy and understood it was going to be a wedding day. Wilmore had actually been worried about the efficiency of the lorry’s response control system thrusters. There are 28 of them. Around the border of Starliner’s service module, at the aft of the automobile, there are 4 “doghouses” similarly spaced around the automobile.

Each of these dog houses includes 7 little thrusters for maneuvering. In each dog house, 2 thrusters are aft-facing, 2 are forward-facing, and 3 remain in various radial instructions (see a picture of a dog house, with the cover got rid of, here). For docking, these thrusters are necessary. There had actually been some issues with their efficiency throughout an uncrewed flight test to the spaceport station in May 2022, and Wilmore had actually been worried those problems may crop up once again.

Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft is envisioned docked to the International Space Station. Among the 4 dog houses shows up on the service module.

Credit: NASA

Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft is imagined docked to the International Space Station. Among the 4 dog houses shows up on the service module.

Credit: NASA

Wilmore: “Before the flight we had a meeting with a lot of the senior Boeing executives, including the chief engineer. [This was Naveed Hussain, chief engineer for Boeing’s Defense, Space, and Security division.] Naveed asked me what is my biggest concern? And I said the thrusters and the valves because we’d had failures on the OFT missions. You don’t get the hardware back. (Starliner’s service module is jettisoned before the crew capsule returns from orbit). So you’re just looking at data and engineering judgment to say, ‘OK, it must’ve been FOD,’ (foreign object debris) or whatever the various issues they had. And I said that’s what concerns me the most. Because in my mind, I’m thinking, ‘If we lost thrusters, we could be in a situation where we’re in space and can’t control it.’ That’s what I was thinking. And oh my, what happened? We lost the first thruster.”

When automobiles approach the spaceport station, they utilize 2 fictional lines to assist direct their technique. These are the R-bar, which is a line linking the spaceport station to the center of Earth. The “R” mean radius. There is the V-bar, which is the speed vector of the area station. Due to thruster concerns, as Starliner neared the V-bar about 260 meters (850 feet) from the spaceport station, Wilmore needed to take manual control of the automobile.

Wilmore: “As we get closer to the V-bar, we lose our second thruster. So now we’re single fault tolerance for the loss of 6DOF control. You understand that?”

Here things get a little bit more complex if you’ve never ever piloted anything. When Wilmore describes 6DOF control, he indicates 6 degrees of flexibility– that is, the 6 various motions possible in three-dimensional area: forward/back, up/down, left/right, yaw, pitch, and roll. With Starliner’s 4 dog houses and their different thrusters, a pilot has the ability to manage the spacecraft’s motion throughout these 6 degrees of flexibility. As Starliner got to within a couple of hundred meters of the station, a 2nd thruster stopped working. The condition of being “single fault” tolerant ways that the car might sustain simply another thruster failure before being at danger of losing complete control of Starliner’s motion. This would require a necessary abort of the docking effort.

Wilmore: “We’re single fault tolerant, and I’m thinking, ‘Wow, we’re supposed to leave the space station.’ Because I know the flight rules. I did not know that the flight directors were already in discussions about waiving the flight rule because we’ve lost two thrusters. We didn’t know why. They just dropped.”

The heroes in Mission Control

As part of the Commercial Crew program, the 2 business offering transport services for NASA, SpaceX, and Boeing, got to choose who would fly their spacecraft. SpaceX picked to run its Dragon automobiles out of a nerve center at the business’s head office in Hawthorne, California. Boeing picked to contract with NASA’s Mission Control at Johnson Space Center in Houston to fly Starliner. At this point, the car is under the province of a Flight Director called Ed Van Cise. This was the capstone objective of his 15-year profession as a NASA flight director.

Wilmore: “Thankfully, these folks are heroes. And please print this. What do heroes look like? Well, heroes put their tank on and they run into a fiery building and pull people out of it. That’s a hero. Heroes also sit in their cubicle for decades studying their systems, and knowing their systems front and back. And when there is no time to assess a situation and go and talk to people and ask, ‘What do you think?’ they know their system so well they come up with a plan on the fly. That is a hero. And there are several of them in Mission Control.”

From the outdoors, as Starliner approached the spaceport station last June, we understood little of this. By following NASA’s webcast of the docking, it was clear there were some thruster problems which Wilmore needed to take manual control. We did not understand that in the last minutes before docking, NASA waived the flight guidelines about loss of thrusters. According to Wilmore and Williams, the drama was just starting at this moment.

Wilmore: “We acquired the V-bar, and I took over manual control. And then we lose the third thruster. Now, again, they’re all in the same direction. And I’m picturing these thrusters that we’re losing. We lost two bottom thrusters. You can lose four thrusters, if they’re top and bottom, but you still got the two on this side, you can still maneuver. But if you lose thrusters in off-orthogonal, the bottom and the port, and you’ve only got starboard and top, you can’t control that. It’s off-axis. So I’m parsing all this out in my mind, because I understand the system. And we lose two of the bottom thrusters. We’ve lost a port thruster. And now we’re zero-fault tolerant. We’re already past the point where we were supposed to leave, and now we’re zero-fault tolerant and I’m manual control. And, oh my, the control is sluggish. Compared to the first day, it is not the same spacecraft. Am I able to maintain control? I am. But it is not the same.”

At this moment in the interview, Wilmore entered into some terrific information.

Wilmore: “And this is the part I’m sure you haven’t heard. We lost the fourth thruster. Now we’ve lost 6DOF control. We can’t maneuver forward. I still have control, supposedly, on all the other axes. But I’m thinking, the F-18 is a fly-by-wire. You put control into the stick, and the throttle, and it sends the signal to the computer. The computer goes, ‘OK, he wants to do that, let’s throw that out aileron a bit. Let’s throw that stabilizer a bit. Let’s pull the rudder there.’ And it’s going to maintain balanced flight. I have not even had a reason to think, how does Starliner do this, to maintain a balance?”

This is a really precarious circumstance we’re in

Basically, Wilmore might not completely control Starliner any longer. Just deserting the docking effort was not a tasty service. Simply as the thrusters were required to manage the automobile throughout the docking procedure, they were likewise needed to place Starliner for its deorbit burn and reentry to Earth’s environment. Wilmore had to consider whether it was riskier to approach the area station or attempt to fly back to Earth. Williams was stressing over the very same thing.

Williams: “There was a lot of unsaid communication, like, ‘Hey, this is a very precarious situation we’re in.’ I think both of us overwhelmingly felt like it would be really nice to dock to that space station that’s right in front of us. We knew that they [Mission Control] were working really hard to be able to keep communication with us, and then be able to send commands. We were both thinking, what if we lose communication with the ground? So NORDO Con Ops (this means flying a vehicle without a radio), and we didn’t talk about it too much, but we already had synced in our mind that we should go to the space station. This is our place that we need to probably go to, to have a conversation because we don’t know exactly what is happening, why the thrusters are falling off, and what the solution would be.”

Wilmore: “I don’t know that we can come back to Earth at that point. I don’t know if we can. And matter of fact, I’m thinking we probably can’t. So there we are, loss of 6DOF control, four aft thrusters down, and I’m visualizing orbital mechanics. The space station is nose down. So we’re not exactly level with the station, but below it. If you’re below the station, you’re moving faster. That’s orbital mechanics. It’s going to make you move away from the station. So I’m doing all of this in my mind. I don’t know what control I have. What if I lose another thruster? What if we lose comm? What am I going to do?”

Among the other difficulties at this moment, in addition to holding his position relative to the spaceport station, was keeping Starliner’s nose pointed straight at the orbital lab.

Williams: “Starliner is based on a vision system that looks at the space station and uses the space station as a frame of reference. So if we had started to fall off and lose that, which there’s a plus or minus that we can have; we didn’t lose the station ever, but we did start to deviate a little bit. I think both of us were getting a bit nervous then because the system would’ve automatically aborted us.”

After Starliner lost 4 of its 28 response control system thrusters, Van Cise and this group in Houston chose the very best opportunity for success was resetting the stopped working thrusters. This is, successfully, an elegant method of shutting off your computer system and restarting it to attempt to repair the issue. It implied Wilmore had to go hands-off from Starliner’s controls.

Think of that. You’re wandering away from the spaceport station, attempting to keep your position. The station is your only genuine lifeline since if you lose the capability to dock, the possibility of returning in one piece is rather low. And now you’re being informed to take your hands off the controls.

Wilmore: “That was not easy to do. I have lived rendezvous orbital dynamics going back decades. [Wilmore is one of only two active NASA astronauts who has experience piloting the space shuttle.] Ray Bigonesse is our rendezvous officer. What a motivated individual. Primarily him, but me as well, we worked to develop this manual rendezvous capability over the years. He’s a volunteer fireman, and he said, ‘Hey, I’m coming off shift at 5:30 Saturday morning; will you meet me in the sim?’ So we’d meet on Saturdays. We never got to the point of saying lose four thrusters. Who would’ve thought that, in the same direction? But we’re in there training, doing things, playing around. That was the preparation.”

All of this training implied Wilmore seemed like he remained in the very best position to fly Starliner, and he did not enjoy the idea of quiting control. Lastly, when he believed the spacecraft was briefly steady enough, Wilmore called down to Mission Control, “Hands off.” Practically right away, flight controllers sent out a signal to bypass Starliner’s flight computer system and fire the thrusters that had actually been shut off. 2 of the 4 thrusters returned online.

Wilmore: “Now we’re back to single-fault tolerant. But then we lose a fifth jet. What if we’d have lost that fifth jet while those other four were still down? I have no idea what would’ve happened. I attribute to the providence of the Lord getting those two jets back before that fifth one failed. So we’re down to zero-fault tolerant again. I can still maintain control. Again, sluggish. Not only was the control different on the visual, what inputs and what it looked like, but we could hear it. The valve opening and closing. When a thruster would fire, it was like a machine gun.”

We’re most likely not flying home in Starliner

Objective Control chose that it wished to attempt to recuperate the stopped working thrusters once again. After Wilmore took his hands off the controls, this procedure recuperated all however among them. At that point, the car might be flown autonomously, as it was planned to be. When asked to quit control of the car for its last technique to the station, Wilmore stated he was worried about doing so. He was worried that if the system entered into automation mode, it might not have actually been possible to get it back in manual mode. That had actually taken place, he desired to make sure he might take control of Starliner once again.

Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams landed in a Crew Dragon spacecraft in March. Dolphins were amongst their greeters.

Credit: NASA

Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams landed in a Crew Dragon spacecraft in March. Dolphins were amongst their greeters.

Credit: NASA

Wilmore: “I was very apprehensive. In earlier sims, I had even told the flight directors, ‘If we get in a situation where I got to give it back to auto, I may not.’ And they understood. Because if I’ve got a mode that’s working, I don’t want to give it up. But because we got those jets back, I thought, ‘OK, we’re only down one.’ All this is going through my mind in real time. And I gave it back. And of course, we docked.”

Williams: “I was super happy. If you remember from the video, when we came into the space station, I did this little happy dance. One, of course, just because I love being in space and am happy to be on the space station and [with] great friends up there. Two, just really happy that Starliner docked to the space station. My feeling at that point in time was like, ‘Oh, phew, let’s just take a breather and try to understand what happened.'”

“There are really great people on our team. Our team is huge. The commercial crew program, NASA and Boeing engineers, were all working hard to try to understand, to try to decide what we might need to do to get us to come back in that spacecraft. At that point, we also knew it was going to take a little while. Everything in this business takes a little while, like you know, because you want to cross the T’s and dot the I’s and make sure. I think the decision at the end of the summer was the right decision. We didn’t have all the T’s crossed; we didn’t have all the I’s dotted. So do we take that risk where we don’t need to?”

Wilmore included that he felt quite positive, in the after-effects of docking to the spaceport station, that Starliner most likely would not be their trip home.

Wilmore: “I was thinking, we might not come home in the spacecraft. We might not. And one of the first phone calls I made was to Vincent LaCourt, the ISS flight director, who was one of the ones that made the call about waiving the flight rule. I said, ‘OK, what about this spacecraft, is it our safe haven?‘”

It was not likely to occur, however if some disastrous spaceport station emergency situation took place while Wilmore and Williams remained in orbit, what were they expected to do? Should they pull away to Starliner for an emergency situation departure, or pack into among the other automobiles on station, for which they did not have seats or spacesuits? LaCourt stated they ought to utilize Starliner as a safe house for the time being. Therein followed a long series of conferences and conversations about Starliner’s viability for flying team back to Earth. Openly, NASA and Boeing revealed self-confidence in Starliner’s safe return with team. Williams and Wilmore, who had actually simply made that traumatic trip, felt in a different way.

Wilmore: “I was very skeptical, just because of what we’d experienced. I just didn’t see that we could make it. I was hopeful that we could, but it would’ve been really tough to get there, to where we could say, ‘Yeah, we can come back.'”

They did not.

Eric Berger is the senior area editor at Ars Technica, covering whatever from astronomy to personal area to NASA policy, and author of 2 books: Liftoffabout the increase of SpaceX; and Reentryon the advancement of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A qualified meteorologist, Eric resides in Houston.

174 Comments

Learn more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.