(Image credit: Fabio Fogliazza)

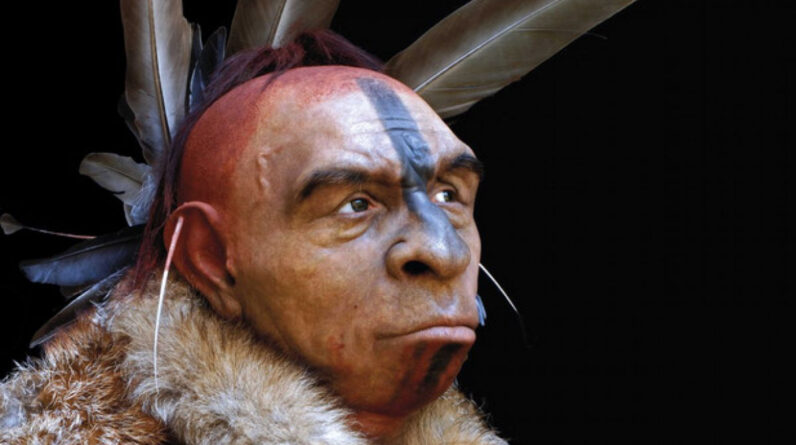

Individuals have actually been interested by Neanderthals since we found their bones in a German collapse the mid-19th century. Their stocky bodies and substantial heads provide us a fun-house-mirror look into the evolutionary roadway we may have taken a trip. Despite the fact that DNA research study has actually revealed that all modern-day human populations have a little Neanderthal in them, we still see our Neanderthal cousins as the black sheep family tree of the Homo genus.

Here’s a take a look at 10 things we’ve learnt more about our closest recognized loved ones– and, by extension, ourselves– this year.

Related: Lucy’s last day: What the renowned fossil exposes about our ancient forefather’s last hours

1. Neanderthals had an eager sense of style.

Neanderthals resided in Europe, so they needed to secure their bodies from frostbite and other cold-related issues. No frozen caveman clothes has actually ever been found, archaeologists believe Neanderthals used clothes to assist preserve their core body temperature level.

Inconclusive evidence of Neanderthal clothes consists of a stone tool with residue from conceal scraping, pointed bone awls utilized to punch holes in hides, and a twisted little cable, perhaps from shoes or material.

The sort of clothes Neanderthals used is still being discussed, however it was likely more intricate than a loin cloth. If Neanderthals were using parkas, trousers and boots, they were most likely the very first fashionistas, scientists informed Live Science.

2. Neanderthals took care of their associates with impairments.

A restoration of a Neanderthal household in a cavern (Image credit: Bjanka Kadic through Alamy Stock Photo)

A piece of a Neanderthal kid’s ear bone recommends she had Down syndrome which she was taken care of by her neighborhood. In a research study released in June in the journal Science Advancesscientists recognized a 6-year-old Neanderthal kid nicknamed “Tina” in a collapse Spain. Tina’s ear bone, which dated to in between 273,000 and 146,000 years back, has actually a shape related to Down syndrome, along with other problems.

No hereditary work has actually conclusively revealed that Tina had Down syndrome, she nonetheless would have needed care from her neighborhood to endure, according to the scientists, because her ear bone likewise recommended she had significant hearing loss and vertigo. The finding recommends that other Neanderthals were assisting her and her mom out of a sense of selflessness.

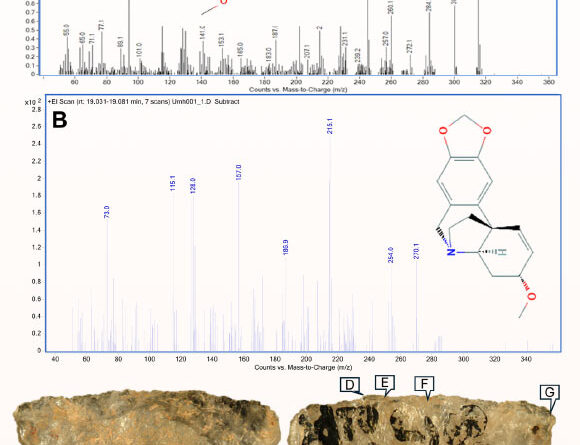

3. Neanderthals produced an early “glue factory.”

A Neanderthal male curates a fire in the dark (Image credit: MARCO BERTORELLO through Getty Images )

As far back as 65,000 years back, Neanderthals on the Iberian Peninsula were knowledgeable engineers who made sticky tar in a specifically regulated environment. In the December problem of the journal Quaternary Science Reviewsscientists detailed their discovery of a hearth in a cavern flooring in Gibraltar. The hearth had plenty of charcoal and plant resin and was most likely warmed to 300 degrees Fahrenheit (150 degrees Celsius) to produce the gooey glue, which would have been utilized to style weapons such as spears.

The findings reveal Neanderthals were both extremely smart and able to team up to produce complex tools.

4. Modern human beings and Neanderthals buried their dead in a different way.

Burial of a Neanderthal at La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France ( Image credit: DEA/ A. DAGLI ORTI/De Agostini by means of Getty Images)

Putting a dead body in a hole and covering it up is a burial practice special to human beings and Neanderthals. Neanderthals buried their dead in a different way than Humankindaccording to research study released this summertime in the journal L’Anthropologie

By taking a look at burials in Western Asia over a period of 85,000 years– when modern-day people and Neanderthals overlapped– scientists observed both resemblances and distinctions. Everybody buried their dead without regard to their sex or age, and both contemporary human beings and Neanderthals put products in their tombs. While Neanderthals buried their dead in a range of positions in caverns, early H. sapiens buried theirs in the fetal position outside caverns.

Neanderthals and H. sapiens began burying their dead throughout the exact same period– about 90,000 to 120,000 years earlier– maybe to mark their area or claim particular resources in a landscape bursting with hominins.

Related: From ‘Lucy’ to the ‘Hobbits’: The most well-known fossils of human family members

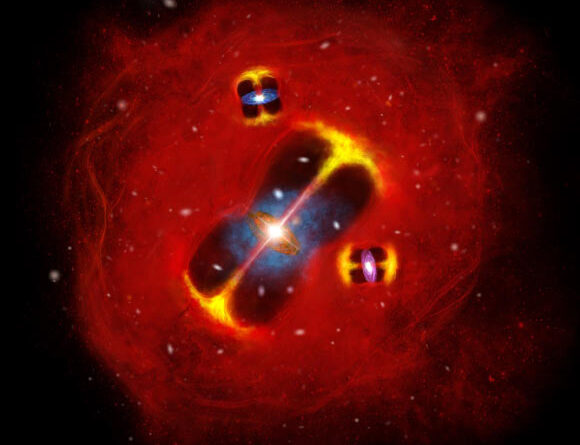

5. They looked a lot like us.

Restoration of the face of Neanderthal’Shanidar Z’on the right along with her skull on the. (Image credit: JUSTIN TALLIS/ Contributor by means of Getty Images)

Various burials discovered in Shanidar Cave in Iraq offer a few of the earliest proof of purposeful interment of the dead. The skull of a lady referred to as Shanidar Z was pieced together from numerous pieces, and her face was rebuilded to offer an image of among our extinct loved ones.

Neanderthal skulls look various from those of contemporary human beings; they have big eyebrow ridges, popular noses and no chin. When muscles and skin are put back on the bone, even essentially, the resemblances in between Neanderthals and human beings are obvious, and their long history of interbreeding is not unexpected.

6. The last Neanderthals were separated.

The jawbone of’Thorin’-among the last Neanderthals – emerging from the dirt (Image credit: Ludovik Slimak)

DNA sequencing of a Neanderthal nicknamed “Thorin” exposed that some groups might have been separated for countless years before going extinct. Found in France’s Rhône Valley, Thorin was dated to in between 52,000 and 42,000 years earlier. His DNA recommended that his family tree was rather inbred, although other Neanderthal groups lived close by.

“How can we imagine populations that lived for 50 millennia in isolation while they are only two weeks’ walk from each other?” stated Ludovic Slimaka scientist at the Center for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse in France and lead author of the research study. “Everything must be rewritten about the greatest extinction in humanity.”

7. Male Neanderthal DNA appears to have actually disappeared without a trace.

Restorations of a human and a Neanderthal in a museum screen case (Image credit: mauritius images GmbH/ Alamy Stock Photo)

Plenty of genes are shared in between modern-day people and Neanderthals, the H. sapiens genome does not have any Neanderthal Y chromosome DNAwhich raises the concern of how and why this hereditary product disappeared.

One interesting possibility is that mating just didn’t work in between Neanderthal males and H. sapiens females. Despite the fact that the 2 groups interbred numerous times over countless years, if a human mom was pregnant with a male Neanderthal infant, her body immune system might have assaulted the male fetus with unidentified Y chromosome genes throughout pregnancy, leading to a miscarriage. Ultimately, if less male Neanderthal hybrid children were born, the Y chromosome genes would vanish.

It is not yet specific why the Neanderthal Y chromosome is no longer in our evolutionary gene swimming pool. Since it is given just from daddy to kid, it might have merely been lost over the generations.

8. Neanderthals were most likely soaked up into modern-human groups.

A restoration of a lady who lived 45,000 years back, around the time Neanderthals likewise existed (Image credit: Tom Björklund )

2 crucial research studies released just recently revealed that, although Neanderthals vanished as a group, much of their genes did not.

By taking a look at more than 300 human genomes from the previous 45,000 years, scientists approximated that the majority of the Neanderthal DNA that continues us is from practically 7,000 years of interbreeding that started around 47,000 years ago

On the other hand, research study released in July in the journal Science approximated that the Neanderthal genome might have been in between 2.5% and 3.7% human, showing that both human and Neanderthal populations had a long history of exchanging mates. The hereditary analysis likewise exposed that the Neanderthal population size was rather little. The finding recommends that, instead of going through a significant termination, the Neanderthals were just soaked up into bigger human groups.

Related: Ancient human forefather Lucy was not alone– she lived along with a minimum of 4 other proto-human types, emerging research study recommends

9. Neanderthal DNA impacts our health.

Illustration of an early contemporary human male accepting a Neanderthal lady (Image credit: Kevin McGivern for Live Science)

Continuous DNA research study likewise exposed that our health is impacted by Neanderthal genesfor much better or for even worse.

People acquired Neanderthal genes for specific pregnancy hormonal agents, which are connected with increased fertility and a lower threat of miscarriage. Other gene versions from our Neanderthal cousins make us more vulnerable to allergic reactions and Type 2 diabetesmore conscious discomfort and sunshine, and most likely to be at threat for nicotine dependencyextreme COVID-19 autoimmune conditions and anxiety

10. Human beings most likely did not exterminate Neanderthals– a minimum of, not straight.

A statue of a Neanderthal male using fur and bring a stick (Image credit: Arterra Picture Library/ Alamy Stock Photo)

We likewise discovered that contemporary human beings didn’t intentionally exterminate the world’s last NeanderthalsIn addition to soaking up a few of the Neanderthals through interbreeding and gene exchange, people appear to have actually just outcompeted Neanderthals by drawing on our large socials media when times was difficult and leaving our shy cousins high and dry.

who was the last Neanderthal? Scientists still do not understand for sure, present proof points to southern Iberia as a prospective place for Neanderthals’ last stand around 37,000 years earlier. After that time, Neanderthals as an unique group disappeared, although they survive on, in part, through the genes they showed us.

Get the world’s most interesting discoveries provided directly to your inbox.

Kristina Killgrove is a personnel author at Live Science with a concentrate on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her posts have actually likewise appeared in locations such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Killgrove holds postgraduate degrees in sociology and classical archaeology and was previously a university teacher and scientist. She has actually gotten awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science composing.

The majority of Popular

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.