Avoid to content

“Some are wolves and some are adders”

“This is very early evidence of a preacher weaving pop culture into a sermon to keep his audience hooked.”

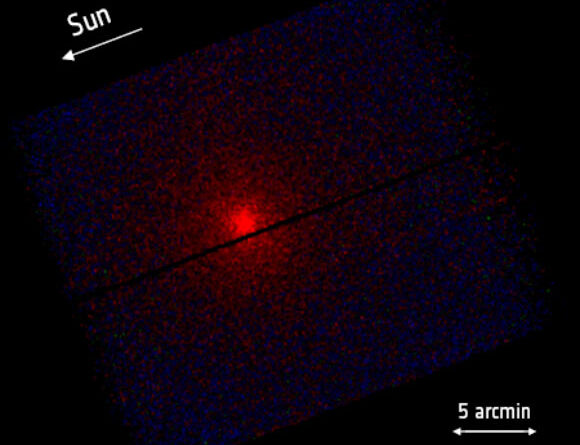

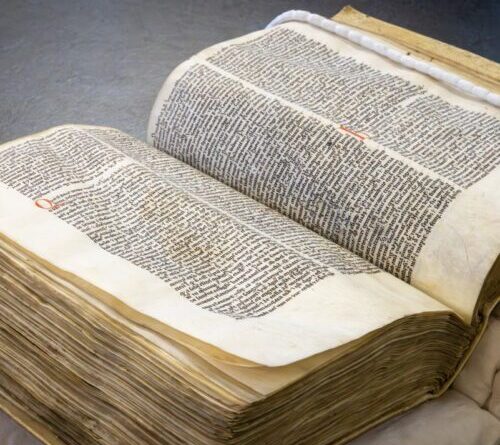

The book, Peterhouse MS 255, open at the preaching’s reference of Wade.

Credit: University of Cambridge

Middle ages poet Geoffrey Chaucer two times referred to an early work including a Germanic mythological character called Wade. Just 3 lines endure, found buried in a preaching by a late 19th century scholar. There has actually been much dispute over how to equate those pieces since, and whether the long-lost work was a monster-filled impressive or a chivalric love. 2 Cambridge University scholars now state those lines have actually been “radically misunderstood” for 130 years, providing their own translation– and argument in favor of a love– in a brand-new paper released in the Review of English Studies.

We understand such a middle ages work when existed due to the fact that it’s referenced in other texts, most significantly by Chaucer. He mentions the “tale of Wade” in his legendary poem Troilus and Criseyde and points out “Wade’s boat [boot]” in The Merchant’s Tale— part of his work of art, The Canterbury TalesA late 16th century editor of Chaucer’s works, Thomas Speght, made a passing remark that Wade’s boat was called “Guingelot,” which Wade’s “strange exploits” were “long and fabulous,” Didn’t elaborate any even more, no doubt presuming the tale was typical understanding and for this reason not worth retelling. Speght’s truncated remark “has often been called the most exasperating note ever written on Chaucer,” F.N. Robinson composed in 1933.

The complete story has actually been lost to history, although some residue information have actually endured. There are points out of Wade in an Old English poem, explaining him as the boy of a king and a “serpent-legged mermaid.” The Poetic Edda points out Wade’s child, Wayland, along with Wayland’s bros Egil and Slagfin. Wade is likewise quickly referenced in Malory’s Morte D’Arthur and a handful of other texts from around the exact same duration. Enjoyable reality: J.R.R. Tolkien based his Middle-earth character Earendil on Wade; Earendil cruises throughout the sky in a wonderful ship called Wingelot (or Vingilot).

In 1896, Cambridge medievalist M.R. James was assembling a brochure of middle ages preachings and kept in mind a passage of English verse in the otherwise Latin text of one such manuscript. (Life mimicked art: James was likewise an author and had actually simply released a ghost story the year before about a Cambridge antiquarian who found a book of unusual, long-lost middle ages texts.)

He sought advice from an associate, Israel Gollancz, who focused on Middle English poetry for a translation: “Some are elves and some are adders; some are sprites that dwell by waters: there is no man, but Hildebrand only.” (Folk legends describe Hidebrande as a giant and Wade’s daddy, who begat him on a mermaid.) They concluded the lines were from a lost early 13th century romantic poem they called The Song of WadeLike Speght before them, James and Gollancz used no additional remark.

A middle ages meme

Seb Falk(l)and James Wade (r)have a look at the manuscript, opened to the preaching.

Credit: University of Cambridge

To Seb Falk and James Wade, authors of the brand-new paper, it’s clear that Wade was a popular chivalric hero throughout the whole duration of Middle English love, and a most likely folk hero. They think about Wade as a sort of middle ages meme. “Romance writers invoke Wade as if he is meant to be recognizable as one of the greatest knights of chivalry,” they composed. The exact same seems real of the confidential pastor who composed the preaching consisting of the three-line piece.

“The preaching itself is actually intriguing,”stated Falk.”It’s an innovative experiment at a defining moment when preachers were attempting to make their preachings more available and fascinating. Here we have a late-12th century preaching releasing a meme from the hit romantic story of the day. This is really early proof of a preacher weaving popular culture into a preaching to keep his audience hooked. I when went to a wedding event where the vicar, intending to interest an audience who he figured didn’t frequently go to church, priced quote the Black Eyed Peas’ tune ‘Where is the Love?’ in an apparent effort to appear cool. Our middle ages preacher was attempting something comparable to get attention and sound pertinent.”

It’s the translation of the word “elves” that is main to their brand-new analysis. Based upon their factor to consider of the lines in the context of the preaching (called the Humiliamini preaching) as an entire, Falk and Wade think the proper translation is “wolves.” The confusion emerged, they recommend, since of a scribe’s mistake while transcribing the preaching: particularly, the letters “y” (“ylves”and “w” ended up being muddled. The preaching concentrates on humbleness, highlighting how human beings have actually been debased because Adam and comparing human habits to animals: the shrewd deceit of the adder, for instance, the pride of lions, the gluttony of pigs, or the plundering of wolves.

The text of the preaching.

Credit: University of Cambridge

Falk and Wade believe equating the word as “wolves” solves a few of the perplexity surrounding Chaucer’s referrals to Wade. The pertinent passage in Troilus and Criseyde issues Pandarus, uncle to Criseyde, who welcomes his niece to supper and regales her with tunes and the “tale of Wade,” in hopes of bringing the fans together. A chivalric love would serve this function much better than a Germanic brave legendary stimulating “the mythological sphere of giants and monsters,” the authors argue.

The brand-new translation makes more sense of the recommendation in The Merchant’s Taletoo, in which an old knight argues for weding a girl instead of an older one due to the fact that the latter are crafty and spin myths. The knight hence weds a much more youthful lady and winds up cuckolded. “The tale becomes, effectively, an origin myth for all women knowing ‘so muchel craft on Wades boot,'” the authors composed.

And while they acknowledge that the proof is circumstantial, Falk and Wade believe they’ve recognized the author of the Humiliamini preaching: late middle ages author Alexander Neckam, or maybe an acolyte mimicing his arguments and composing design.

Evaluation of English Studies, 2025. DOI: 10.1093/ res/hgaf038 (About DOIs).

Jennifer is a senior author at Ars Technica with a specific concentrate on where science satisfies culture, covering whatever from physics and associated interdisciplinary subjects to her preferred movies and television series. Jennifer resides in Baltimore with her partner, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their 2 felines, Ariel and Caliban.

56 Comments

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.