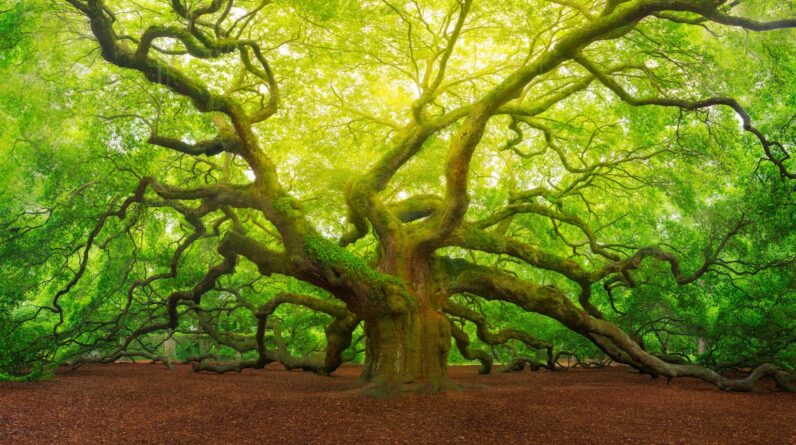

(Image credit: Piriya Photography through Getty Images)

In this excerpt from “Oak Origins: From Acorns to Species and the Tree of Life” (University of Chicago Press, 2024 ), author Andrew L. Hipp checks out the severe conditions in the world that generated the oak tree(Quercuswith wild changes in the environment and moving tectonic plates.

If we might head back in time 56 million years and invest a couple of weeks botanizing in the temperate forests of the Northern Hemisphere, at the limit in between the Paleocene and the Eocene, we would be hard-pressed to discover any oaks. We would discover alligators and huge tortoises on Ellesmere Island, throughout from the northwest coast of Greenland. We would stroll through flowering-plant-dominated forests whose variety approached the plant variety we may discover in the modern-day forests of the southeastern United States. We would experience a variety of Fagales, family trees spreading out throughout the Northern Hemisphere that would ultimately generate walnuts, birches, sweet windstorms, beeches, chestnuts, chinkapins, and oaks.

The oaks themselves, nevertheless, were so couple of in number at that point that they left little if any pollen in the mud and no acorns or delegates be recuperated by 21st-century botanists. The world will get in a heatwave, the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM).

Throughout 8,000 to 10,000 years, climatic temperature levels would increase, increasing by approximately 8 degrees C [14.4 degrees Fahrenheit] around the world and reaching even greater levels in the Arctic. The PETM might have been set off by a huge and drawn-out duration of volcanic activity. Lava gurgling up through a crack at the bottom of the North Atlantic drove a wedge in between North America and Europe and put a trillion kgs [2.2 trillion pounds] of carbon into the environment every year for a number of thousand years.

Increasing temperature levels melted remains out of the Antarctic permafrost, and the decomposing sedges, sphagnum mosses, fungis and lichens, mollusks and marsupials returned greenhouse gases– co2 and methane– to the environment.

Temperature levels then crashed back to their initial levels within about 120,000-220,000 years. That’s hardly enough for a double take in geological terms: When you take a look at a temperature level plot for the previous 100 million years, the PETM appears like a fencepost driven into the hillside 56 million years back. It goes directly up and practically directly pull back.

The results were remarkable. The PETM drove 30%-50% of deep-ocean-bottom foraminifera– single-celled organisms that occupy the seas, consuming plankton and sediment, feeding little fish and marine snails– extinct. Mammals, lizards, and turtles moved commonly throughout the continents in reaction to the altering environments, taking a trip in between northern land bridges that would end up being too cold for routine travel by the majority of these types in the late Eocene.

Get the world’s most remarkable discoveries provided directly to your inbox.

In northern South America, tropical forests were flooded with brand-new blooming plants: palms, turfs, and the Bean Family (Fabaceae) all increased in variety in the Eocene, and the Spurge Family– Euphorbiaceae, a worldwide household that numbers about 6,500 types today– appeared in northern South America for the very first time throughout the PETM.

The very first oak fossils

Insect herbivores, especially leaf miners and surface area feeders, increased in abundance and ended up being more specialized. Plants raced throughout the landscape: in Bighorn Basin, Wyoming, a minimum of 22 types were extirpated at the start of the PETM, just to return after the occasion was over. A few of these sojourners moved an approximated 1,000 kilometers [600 miles]

The very first fossil oaks we understand of appear in this unsure world, along what is now a treking path running south of the Church of Saint Pankraz in Oberndorf, Austria. Fifty-six million years back, this location of Europe was dissected into islands and peninsulas, which were warmed by the ocean.

The very first fossil oaks we understand of originated from Oberndorf, Austria. (Image credit: elzauer/Getty Images)

What is now Saint Pankraz lay underneath shallow water at the edge of the sea. It ended up being a repository for pollen from nearby forests, transferred along with oceanic plankton and dinoflagellates. The forest growing in the location was a mosaic of subtropical and temperate types, consisting of members of the Restionaceae, a grass-like household that today is restricted to the Southern Hemisphere tropics; Eotrigonobalanusan extinct genus of the Beech Family that previously varied throughout eastern North America and Europe; and loved ones these days’s Cashew Family, Mallow Family, and the pantropical Sapotaceae.

The world was getting in the last days of the almost worldwide tropics. For 4 million years after temperature levels pulled back from the PETM, the environment continued to warm. By 52 million years earlier, the world struck the greatest temperature levels because the death of the dinosaurs. This duration of heat is called the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum.

If the PETM resembles a fencepost driven into the temperature level hillside, the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum resembles the crest of the hill. Forests of tropical types growing together with genera of the temperate forest– maples, elms, walnuts, birches, cherries, and ultimately oaks– spread out throughout the high Arctic. The long winter season nights preferred types that might go inactive for months at a time. Deciduous forests spread out throughout upland websites that are now permafrost and boreal forest.

The oaks we understand today are the outcome of countless years of natural choice. (Image credit: Valentina Shilkina/Getty Images)

The environment was set down at the top of a long slide to the Anthropocene, where we discover ourselves today. Oaks were leaders in what would end up being the mainly temperate Northern Hemisphere.

The oaks were not born at a specific minute or in a specific location. Rather, someplace throughout or before the PETM, a population of woody plants slowly ended up being the oaks. Each seedling in this family tree appeared like the trees that produced it. Had we existed to witness the advancement of that ancestral population, we might at no point have actually stated, “There were no oaks yesterday, but today there are.”

Related: Where did the 1st seeds originate from?

We wound up with oaks by the stable work of natural choice acting upon variable tree populations over extended periods of time. This family tree of people and populations gradually ending up being the oaks is called the stem of the oak clade. It is represented on the Tree of Life by a single line.

The population of trees that transferred the St. Pankraz pollen might represent a sprig growing from that stem or one that grew really near the crown of the oaks. The St. Pankraz pollen is, for now, our finest bet about how old the oaks are. Oaks most likely return a minimum of a bit longer than these fossils, older than the PETM: fossils are tough to discover, so it’s affordable to presume that we might have missed out on some older ones. These fossils supply us a landmark by which to date the oak tree of life.

The very first speciation occasion we understand of in oaks most likely took place within 8 million years of the St. Pankraz oak fossil. It divided the oaks into 2 family trees: one that is today restricted to Eurasia and North Africa, and one that developed in the Americas and just later on went back to Eurasia. Sis clades– which are born as sibling types– can occur in apart geographical areas when their ancestral population ends up being physically partitioned. A range of mountains, a river, a desert, an area of ocean, or any other barrier in between the 2 parts of the population keeps seeds and pollen from moving in between the 2 brand-new populations. Speciation and the birth of brand-new clades typically result.

The dispersing Atlantic Ocean is a possible description for this very first oak speciation occasion. Lava spilling into the North Atlantic off the coast of Ireland at the start of the PETM included crust to the east edge of the North American (tectonic) Plate and the west edge of the Eurasian Plate. It continues to do so today, guiding the continents apart at a rate of about an inch a year.

As the Atlantic grew broader, the ancestral population of all of today’s oaks might have been straddling the continents of the Northern Hemisphere. If so, the forefather of the oaks we understand today was a prevalent population that was cleaved in half as North America inched westward.

Disclaimer

Reprinted with authorization from Oak Origins: From Acorns to Species and the Tree of Life by Andrew L. Hipp, released by The University of Chicago Press. © 2024 by Andrew L. Hipp. All rights booked.

Andrew L. Hippis herbarium director and senior researcher in plant systematics at the Morton Arboretum along with speaker at the University of Chicago. Hipp’s imaginative work has actually appeared in Arnoldia, Scientific American, International Oaks: The Journal of the International Oak Society, Places Journal, and his nature blog site, A Botanist’s Field Notes. He is the author of Field Guide to Wisconsin Sedgesand sixteen kids’s books on a range of nature subjects.

Many Popular

Learn more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.