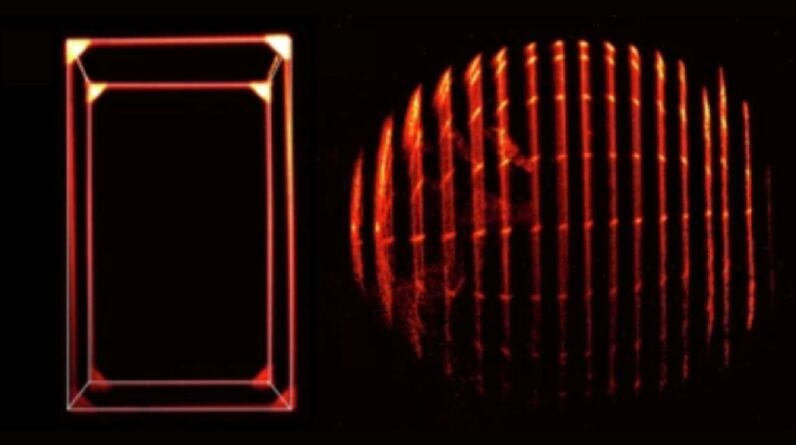

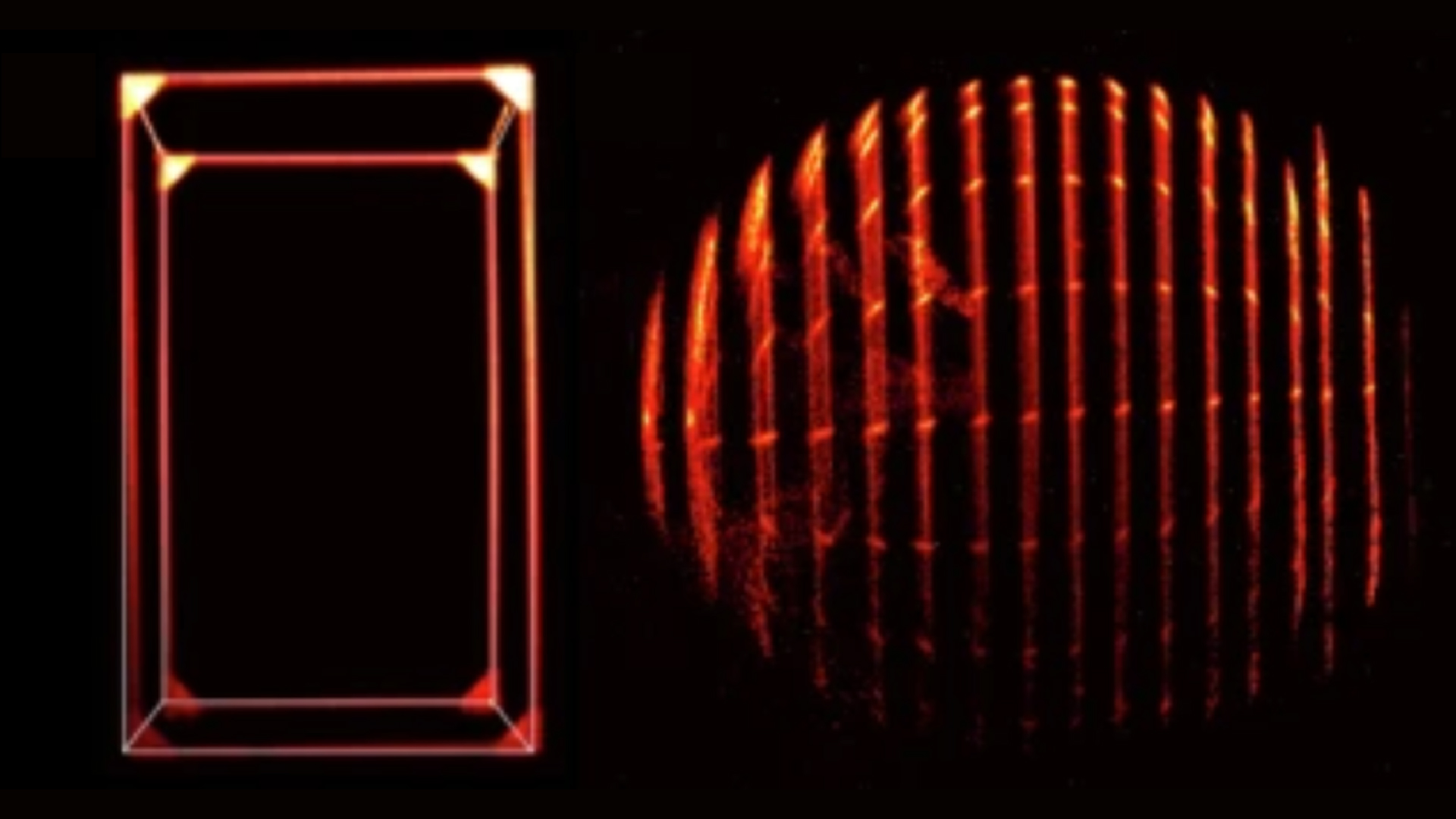

pieces of light to produce photos. At rest(left), the cube looks typical. When simulated at 99.9%of light speed(right), a sphere still looks round however exposes parts of its far side.

(Image credit: Hornof et al., 2025; CC BY 4.0 )

Utilizing ultra-fast laser pulses and unique video cameras, researchers have simulated a visual fallacy that appears to defy Einstein’s theory of unique relativity

One effect of unique relativity is that fast-moving things ought to appear reduced in the instructions of movement– a phenomenon referred to as Lorentz contraction.

This result has actually been verified indirectly in particle accelerator experiments.

Previous designs have actually worked with this impression, now called the Terrell-Penrose impact, this is the very first time it has actually been done in a laboratory setting. The group explained their lead to the journal Communications Physics

“What I like most is the simplicity,” Dominik Hornofa quantum physicist at the Vienna University of Technology and very first author of the research study, informed Live Science. “With the right idea, you can recreate relativistic effects in a small lab. It shows that even century-old predictions can be brought to life in a really intuitive way.”

Re-creating the impressionIn the brand-new research study, physicists utilized ultra-fast laser pulses and gated video cameras to produce pictures of a cube and a sphere “moving” at almost the speed of light. The outcomes revealed photos of turned things. This showed the Terrell-Penrose impact to be real.

The scientists fired ultra-short laser pulses at their test item and after that utilized a hold-up generator to inform the electronic camera precisely when to open its shutter(for simply billionths of a 2nd). This electronic camera caught single pieces of light bouncing off the item. They duplicated the procedure and moved the item in between shots. The group developed the impression of an item racing at near light speed. ( Image credit: Hornof et al., 2025; CC BY 4.0)

The group utilized a smart alternative. “What we can do is mimic the visual effect,” Hornof stated. They began with a cube of about 3 feet (1 meter) on each side. They fired ultra-short laser pulses– each simply 300 picoseconds long, or about a tenth of a billionth of a 2nd– at the things. They recorded the shown light with a gated video camera that opened just for that immediate and produced a thin “slice” each time.

After each piece, they moved the cube forward about 1.9 inches (4.8 cm). That is the range it would have taken a trip if it were moving at 80% the speed of light throughout the hold-up in between pulses. The researchers put all of these pieces together into a photo of the cube in movement.

“When you combine all the slices, the object looks like it’s racing incredibly fast, even though it never moved at all,” Hornof stated. “At the end of the day, it’s just geometry.”

They duplicated the procedure with a sphere, moving it by 2.4 inches (6 cm) per action to simulate 99.9% light speed. When the pieces were integrated, the cube appeared turned and the sphere appeared you might peek around its sides.

“The rotation is not physical,” Hornof stated. “It’s an optical illusion. The geometry of how light arrives at the same time tricks our eyes.”

That is why the Terrell-Penrose impact does not oppose Einstein’s unique relativity. A fast-moving item is physically reduced along its instructions of travel, however an electronic camera does not record that straight. Due to the fact that light from the back takes longer to show up than light from the front, the picture shifts in a manner that makes the things appear turned.

“When we did the calculations, we were surprised how beautifully the geometry worked out,” Hornof stated. “Seeing it appear in the images was really exciting.”

Larissa G. Capella is a science author based in Washington state. She acquired a B.S. in physics and a B.A. in English imaginative writing in 2024, which allowed her to pursue a profession that incorporates both disciplines. She reports primarily on ecological, Earth and physical sciences, however is constantly ready to blog about any science that triggers her interest. Her work has actually appeared in Eos, Science News, Space.com, to name a few.

Learn more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.