( Image credit: Dave Lovelace, CC-BY 4.0)

Around 230 million years earlier, a minimum of 19 alligator-size amphibians ended together on an ancient floodplain in what is now Wyoming.

The animals’fossilized remains, exposed throughout 4 excavations in between 2014 and 2019, have actually been reasonably undisturbed ever since and function maintained fragile little bones and parts of the animals ‘general skeletal structure. The unspoiled findings might supply insight into how these Triassic amphibians lived and matured, scientists reported in a brand-new research study released Wednesday (April 2) in the journal PLOS One

Research study initially author Aaron Kufnera geologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and coworkers exposed fossils of Buettnererpeton bakeri in a Wyoming fossil bed called Nobby Knob. These alligator-size animals come from an ancient amphibian group called metoposaurids, a household of big, primitive four-legged amphibians. B. bakeri is the earliest recognized North American metoposaurid. It lived throughout the Triassic duration (252 million to 201 million years ago) and might have often visited freshwater lakes and rivers as reproducing premises.

It’s relatively typical to discover big stacks of bones, referred to as bone beds, in the fossil record. Generally, bone beds happen when streaming water deposits bones in the exact same location over several years. Other times, bone beds take place when a group of animals pass away at the exact same time and location– which seems the case at Nobby Knob.

“This assemblage is a snapshot of a single population rather than an accumulation over time,” Kufner stated in a declarationThe discovery “more than doubles the number of known Buettnererpeton bakeri individuals.” Along with the B. bakeri fossils, the group likewise discovered fossilized plants, bivalves and fossilized poop, called coprolites.

The amphibian bones didn’t reveal any indications of having actually been moved by streaming water, recommending these animals came to rest in or near calm waters and were gradually buried by great sediments throughout duplicated floods. This left a few of the fossils in the very same shape and plan as the animals’ real skeletons. The scientists discovered B. bakeri fossils of different sizes, which might assist describe how the animals grew and aged.

Since the carefully organized bones weren’t reached the website by currents, the scientists presume the animals died around the exact same time. They might have belonged to a reproducing nest or passed away due to the fact that they were in some way avoided from leaving a drying body of water they required to make it through, the group recommended. It’s still uncertain whether mass metoposaurid die-offs like the one at Nobby Knob prevailed throughout the Triassic or whether the website represents a separated occasion.

Get the world’s most interesting discoveries provided directly to your inbox.

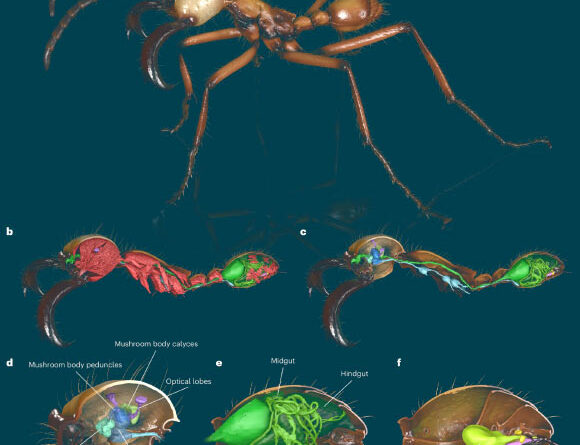

A few of theBuettnererpeton bakerifossilized skulls from the Nobby Knob bone bed. (Image credit: Kufner et al., 2025, PLOS One, CC-BY 4.0)

The B. bakeri fossils might assist researchers date other metoposaurid fossils, the scientists composed in the research study. The Buettnererpeton fossils were buried much deeper than fossils of Anaschisma brownianother metoposaurid, in the Popo Agie Formation– a Triassic development that covers parts of Wyoming, Colorado and Utah. The finding that the Buettnererpeton fossils were most likely older than Anaschisma associates with other fossil beds that protect both types and aid date the areas and depths at which those fossils were discovered.

The Nobby Knob bone bed “preserves a wide size range of individuals from a single site that can provide insight into the [development] of metoposaurids,” the researchers composed in the research study.

Skyler Ware is a freelance science reporter covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has actually likewise appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, to name a few. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

More about extinct types

Find out more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.