enzymes for hormonal agent production.

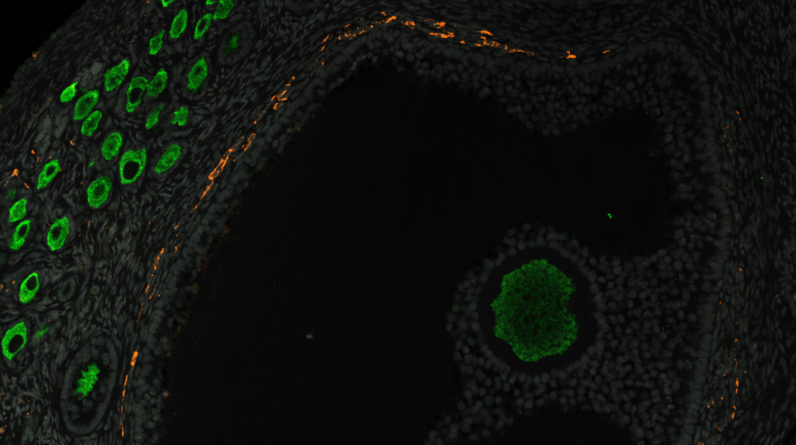

(Image credit: Sissy Wamaitha )

Researchers are one action more detailed to comprehending how human ovaries establish their life time supply of egg cells, called ovarian reserve.

The brand-new research study, released Aug. 26 in the journal Nature Communicationsmapped the introduction and development of the cells and particles that turn into the ovarian reserve in monkeys, from the early phases of ovarian advancement in an embryo to 6 months after birth.

This map fills out a few of the blanks in “really important areas of just unknown biology,” research study co-author Amander Clarka developmental biologist at UCLA, informed Live Science.Scientists can now utilize this map to develop much better designs of the ovary in the laboratory to study reproductive illness associated to the ovarian reserve, she stated, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)– a complicated hormone condition that can lead to infertility.Mystical advancementOvaries are the main female reproductive organs and play 2 important functions in female health and recreation: making egg cells; and making sex hormonal agents, consisting of estrogen, progesterone and testosterone.

Ovaries initially start to establish in embryos around 6 weeks after fertilizationIn the early phases, bacterium cells– which become egg cells– divide and link to one another in intricate chains called nests. When these nests rupture open, specific egg cells are launched and are enclosed by a layer of specialized cells called pregranulosa cells, which support the young eggs and signal when it’s time to develop.

These eggs surrounded by pregranulosa cells are called primitive roots, and are what comprise the ovarian reserve.

Get the world’s most interesting discoveries provided directly to your inbox.

Prehistoric roots begin to form around 20 weeks after fertilization, and cluster on the within edges of the ovaries. When the hair follicles closest to the center of the ovary in these clusters grow, they grow and produce sex hormonal agents.

It is the prehistoric hair follicles that make sure the ovaries perform their tasks of producing fully grown eggs and launching hormonal agents, Clark stated.

Several ovarian illness and conditions are rooted in issues with the cells in the ovarian reserve. Although the precise cause of PCOS is still unidentified, it includes dysfunction in the prehistoric hair folliclesAnd yet, extremely little work has actually been done to comprehend their advancement.

Constructing a map of how and when the ovarian reserve kinds throughout pregnancy can assist find out why specific illness and problems with fertility surface later on in life. “That’s where this study came in,” Clark stated.

Related: First ‘atlas’ of human ovaries might result in fertility advancement, researchers stateSurprise findingsTo examine how ovarian reserves come from primates, Clark and her group took a look at a monkey types that is physiologically comparable to people. This makes it a great stand-in for what takes place developmentally in human beings, she stated.

Female monkey embryos and fetuses were gathered at different developmental phases and ovarian tissue samples were taken. The scientists concentrated on numerous essential time points: day 34 (when the sex organs end up being either male or female), 41 (early ovarian development), 50-52 (end of embryonic duration), 100 (when the egg nest broadens) and 130 (when the nest bursts and the prehistoric hair follicles form) after fertilization.

The group examined the position and molecular finger print of the ovarian cells to comprehend the crucial occasions in the development of the ovarian reserve.

They discovered that pregranulosa cells formed in 2 waves, however it was just throughout the 2nd wave, in between days 41 and 52, that pregranulosa cells formed that would go on to swarm the young eggs to form primitive hair follicles.

They likewise determined 2 genes that appear to be active previous to this 2nd wave. The scientists stated that looking even more into the function of these genes might assist to identify the developmental origins of ovarian reserve issues.

Clark stated the group was entirely shocked to discover that “before birth, the ovary goes through practice rounds of folliculogenesis,” implying that soon after the ovarian reserve is made, a few of the more centrally situated hair follicles grow and can produce hormonal agents. The scientists recommend that figuring out why these hair follicles typically trigger might offer insight into the reasons for PCOS.

Still, the scientists are taking a look at an extremely vibrant duration in advancement, when the cellular makeup of an embryo can alter significantly, Luz Garcia-Alonsoa computational biologist at the Wellcome Sanger Institute who was not associated with the research study, informed Live Science in an e-mail. And they have huge time spaces in between their observation durations.

“This stage when cell lineages are specified is very dynamic, and cell composition changes within days,” Garcia-Alonso stated. The group ought to gather more fine-scale information on more time points to get a much better photo of what is going on, she included.

This short article is for informative functions just and is not suggested to use medical suggestions.

Sophie is a U.K.-based personnel author at Live Science. She covers a vast array of subjects, having actually formerly reported on research study covering from bonobo interaction to the very first water in deep space. Her work has actually likewise appeared in outlets consisting of New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers’ 2025 “Newcomer of the Year” award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before ending up being a science reporter, she finished a doctorate in evolutionary sociology from the University of Oxford, where she invested 4 years taking a look at why some chimps are much better at utilizing tools than others.

Learn more

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.