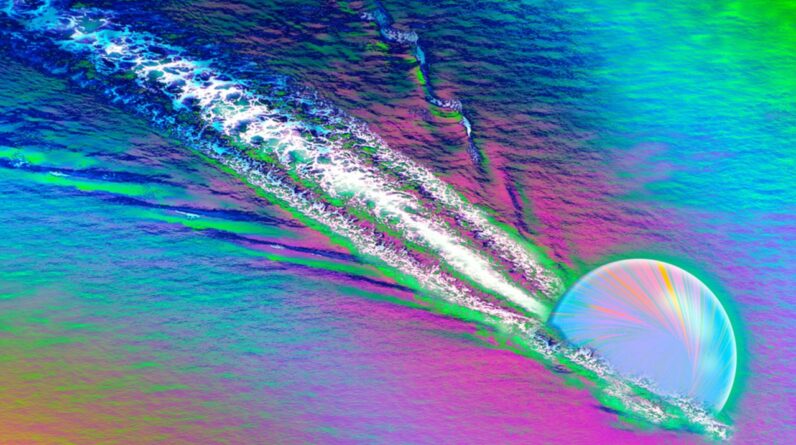

(Image credit: dorioconnell through Getty Images)

Some individuals simply can’t stop scratching after they’re bitten by a mosquito– however not everybody gets scratchy after a bug bite or comparable allergy-triggering encounter. Now, brand-new research study in mice identifies distinctions in body immune system activity that might identify whether you wind up scratchy.

The skin is largely occupied with sensory nerve cellswhich are afferent neuron that identify modifications in the environment and after that set off feelings, such as discomfort, in action. When an individual comes across a possible irritant, like mosquito salivathese nerve cells spot it and might activate a scratchy feeling in reaction. They likewise assist trigger close-by immune cellswhich begin an inflammatory response including swelling and soreness.

Some individuals who are consistently exposed to an irritant can establish persistent allergic swellingwhich basically alters the tissues where that swelling is raving. The immune cells that react to irritants can alter the nerves’ level of sensitivity, making them more or less most likely to respond to a compound.

“We all have sensory nerve cells, so we can all feel scratchy– however not everyone get allergic reactions, although we’re surrounded by the exact same irritants,” senior research study author Dr. Caroline Sokola teacher of allergic reaction and immunology at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, informed Live Science. “So what specifies whose sensory nerve cells fire in action to irritants and whose do not?”

Related: Could allergic reactions be ‘erased’ at some point?

To discover, Sokol and associates exposed mice to a chemical called papainwhich triggers a scratchy feeling that makes mice scratch their skin. The various groups of laboratory mice in the research study were missing out on various immune cells. The research study, released Wednesday (Sept. 4) in the journal Naturediscovered that mice that did not have a particular kind of T cell didn’t scratch when they were exposed to papain.

The scientists wished to learn how these cells, called GD3 cells, drove sensory nerve reactions. They grew GD3 cells in the laboratory and treated them with a chemical to make them launch signifying particles called cytokinesThey injected mice with regular immune systems with the cytokine-containing liquid the cells were grown in.

This treatment didn’t activate itching by itself. It did magnify the mice’s scratching actions to a range of irritants, consisting of mosquito spit. This recommended that something launched by GD3 cells raised the nerve-induced itching.

By comparing the chemicals produced by GD3 cells with those from other immune cells in the main layer of the skinthe scientists found that just one aspect was distinct to the GD3 cells: interleukin 3 (IL-3), which is understood to assistance control swelling

Just some sensory nerve cells reacted to IL-3. Those that did react ended up being most likely to set off an itch– an indication that the cytokine “primes” nerve cells to respond to irritants.

On the other hand, when the scientists got rid of the genes for IL-3 or its receptors– or eliminated the GD3 cells totally– the mice might not start an allergic reaction. With additional experiments, the scientists concluded that IL-3 triggers 2 different signals: one that promotes the nerve-driven itching and another that manages the immune side of the allergic action.

By launching IL-3, the GD3 cells were “definitely vital” for setting the limit at which a sensory nerve would respond to an irritant, Sokol stated. This domino effect including IL-3 “might provide us a brand-new path to deal with clients with persistent itch conditions,” she included.

So far, the research study has actually been performed just in mice, so the scientists can’t be particular that human cells will act the specific very same method. The mouse immune cells in the research study have really comparable genes and proteins as their human equivalents, Sokol stressed that it is very important to comprehend whether and how human T cells respond to IL-3. That information is required to equate the finding into itch treatments or methods to forecast who may be at danger of allergic reactions.

“We all have that good friend who does not respond to mosquito bites and the pal who looks dreadful after a day outside,” Sokol stated. “We think [the IL-3 pathway] is figuring out that in genuine time, due to the fact that when we take a look at mosquito bite-induced itch– and the allergic immune action that follows– we see that it is totally based on the cells in this path.”

Ever question why some individuals construct muscle more quickly than others or why freckles come out in the sunSend us your concerns about how the body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line “Health Desk Q,” and you might see your concern addressed on the site!

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.